Overview

Australian businesses and government departments serve as an attractive target for cyber criminals, and despite best efforts, cyber attacks continue to increase in speed, frequency and complexity.

Some of the reasons for persistent vulnerabilities in organisations include cost, resource constraints, legacy infrastructure, and misunderstandings about cyber security risks and threat levels.

To combat this, the Australian Signals Directorate (ASD) developed the Essential Eight framework.

CyberCX understands implementing the Essential Eight framework can be complex for some organisations.

This guide provides cyber security professionals and decision-makers within Australian businesses and public sector organisations a clear direction on Essential Eight implementation.

It offers practical strategies, insights, and recommendations, promoting a clear understanding of ASD’s Essential Eight controls and helps align organisational goals with Essential Eight objectives.

CyberCX’s Unlocking the Essential Eight covers:

- Essential Eight Overview: A high-level introduction to the Essential Eight’s origins, each of the eight controls and how they work together.

- Essential Eight Application: Guidance on how Essential Eight strategies apply to all organisations, government, private or public.

- Essential Eight Controls/Mitigation Strategies: Maturity level guidance on the Essential Eight controls, mitigation strategies, and pathways to achieving optimal maturity.

- How CyberCX can help: Practical guidance on how CyberCX can assist Australian businesses and government in efficiently navigating and executing cyber security strategies to achieve their desired Essential Eight maturity level.

Origins of the Essential Eight

The foundation of the Essential Eight was established by the Defence Signals Directorate’s (DSD) Cyber Security Operations Centre (CSOC), now known as the Australian Signals Directorate’s Australian Cyber Security Centre (ASD’s ACSC).

DSD developed a list of 35 strategies to reduce the impact of cyber intrusions.

First published in February 2010, the 35 Strategies to Mitigate Targeted Cyber Intrusion, were based on DSD’s analysis of reported security incidents and vulnerabilities detected in testing the security of Australian Government networks.

By 2012, DSD’s promotion of the 35 Strategies shifted to the Top 4 Strategies to Mitigate Targeted Cyber Intrusions, and were made mandatory for Australian Government agencies to implement by April 2013. In the CSOC’s final publication, the language shifted again from a focus on Government to the broader Australian economy.

Fast forward to 2017, the ASD’s ACSC changed the language from Strategies to Mitigate Targeted Cyber Intrusions to Strategies to Mitigate Cyber Security Incidents and published the Essential Eight Maturity Model.

The guidance from the ASD’s ACSC has been designed to assist organisations in protecting their systems against a range of adversaries, including both external actors and insiders, by both malicious and accidental means.

As the threat of a cyber incident continues to remain highly relevant to every sector of the economy.

Evolution of Essential Eight Maturity Model

- February, 2010: 35 Strategies To Reduce The Impact Of Cyber Intrusions.

- October, 2012: Top 4 Strategies to Mitigate Targeted Cyber Intrusions.

- April, 2013: PSPF Policy 10 mandated Top Four Mitigation Strategies.

- June, 2017: Essential Eight Maturity Model developed.

- November, 2019: Policy 10 requirement to consider all of the mitigation strategies.

- October, 2020: Essential Eight Maturity Model includes Maturity Level One, Two and Three.

- July, 2021: Essential Eight Maturity Model includes Maturity Level Zero and baselines Maturity Level Two.

- July, 2022: Policy 10 mandates all Essential Eight mitigation strategies and Essential Eight Maturity Model Level Two Baseline.

Overview of the Essential Eight

The Essential Eight is a set of cyber security controls developed and regularly updated based on ASD’s expertise and experience of the actions they observe taken by threat actors across the Australian economy.

The Essential Eight strategies are designed to be equally impactful for government, private and public organisations.

While no framework can guarantee an organisation will never be compromised, implementing the Essential Eight is intended to increase the cost a threat actor would incur to gain access to your environments.

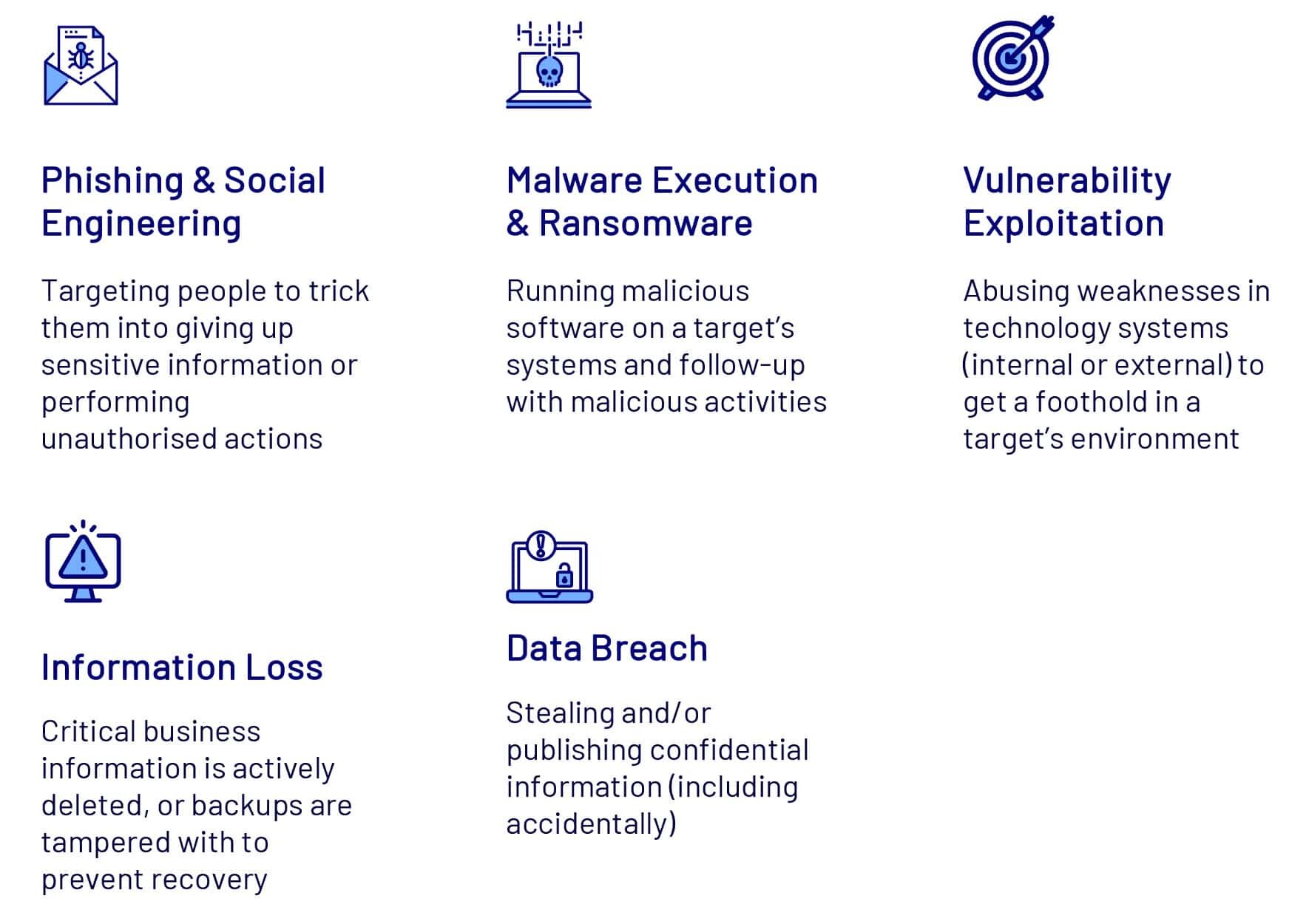

High Level Risk Mitigation Strategies

The Essential Eight is aimed to address a number of specific threats which are known to result in significant business consequences without suitable mitigating controls.

Common Threats Mitigated by the Essential Eight

The Essential Eight Maturity Model

As the Essential Eight strategies are designed to increase the cost to an attacker in compromising systems, they too cannot be implemented without cost.

Acknowledging different organisations have different risk profiles and different types of data to protect, the ASD produced the Essential Eight Maturity Model (E8MM).

A risk-based approach is essential for implementing the Essential Eight effectively. Organisations should strive to minimise exceptions by applying compensating controls and limiting their impact on systems and users. Any exceptions should be documented, formally approved, and reviewed regularly by decision makers to ensure their continued necessity and effectiveness to protect the organisation.

Many organisations CyberCX work with have multiple environments (production, development, testing) which don’t always use the same technology. This might mean that you will need to consider how you progressively increment the controls and maturity levels across your organisation. Identification of high value assets in your environment is a good first place to start.

As the Essential Eight provides a foundational set of preventative measures, organisations should implement additional controls where needed to address risks specific to their environment. While the Essential Eight helps mitigate most cyber threats, it does not eliminate all risks. Therefore, organisations should consider supplementary mitigation strategies.

Important: Having approved exceptions does not prevent an organisation from meeting the requirement of a given maturity level.

To support organisations in implementing the Essential Eight, four maturity levels have been established, starting at Maturity Level 0 to Maturity Level 3.

Except for Maturity Level 0, these levels are designed to mitigate increasingly sophisticated tradecraft, including the tools, tactics, techniques, and procedures used by adversaries.

When adopting the Essential Eight, organisations should define a target maturity level aligned with their specific environment. Since the Essential Eight mitigation strategies are designed to work together and address a broad range of cyber threats, organisations should aim to implement them consistently at the same maturity level before progressing to the next levels.

Insight

The CyberCX DFIR 2025 Threat Report found Multi-Factor Authentication (MFA) didn’t slow down Business Email Compromise (BEC). BEC continued to be the most common incident responded to in 2024. 75% of these incidents involved session hijacking – a method of bypassing MFA. This is a significant increase from 38.5% in 2023.

Maturity Level based on threat actors

Malicious actors may adapt their tradecraft based on their objectives, using advanced techniques against high-value targets while employing more basic methods against others.

Therefore, rather than focusing on specific threat actors, organisations should assess the level of tradecraft and targeting they need to defend against when determining their target maturity level.

The maturity levels have been summarised:

To achieve a specific maturity level, the organisation must effectively implement all the controls within that maturity level and any lesser maturity level controls. For example, an organisation wishing to achieve target Maturity Level 2 must effectively implement all controls under Maturity Level 1 and Maturity Level 2.

TIP: To help establish the optimal target maturity level for your organisation, CyberCX recommends decision makers consider business information holdings including operations, intellectual property, scientific and research data. Other factors to consider are applicable mandatory regulatory or legislative requirements, previous cyber security incidents and threat landscape.

Finally, Maturity Level 3 will not stop malicious actors who are willing and able to invest enough time, money and effort to compromise a target.

As such, organisations still need to consider the remainder of the mitigation strategies from the Strategies to Mitigate Cyber Security Incidents and the ASD suggest looking at additional controls which can be found in the Information Security Manual (ISM).

Did you know?

Phishing-as-a-Service (PhaaS) kits are providing low skilled actors an entry point to an extremely profitable industry. The commoditisation of cybercrime, including ‘as-a-service’ phishing kits, lowers the technical barrier to entry. For the last three years, CyberCX has seen phishing kits with session hijacking capabilities grow continuously in targeting organisations through BEC. Reference: CyberCX DFIR 2025 Threat Report

Who is the Essential Eight for?

In addition to being broadly applicable to any organisation, implementing the Essential Eight may be required or desired for the following:

- Government departments and agencies –federal, state and local; and

- Private and public businesses – small, medium and large organisations.

An organisation may be required to achieve a certain maturity level or may desire to achieve a certain maturity level after assessing the likelihood and consequence of a cyber security incident.

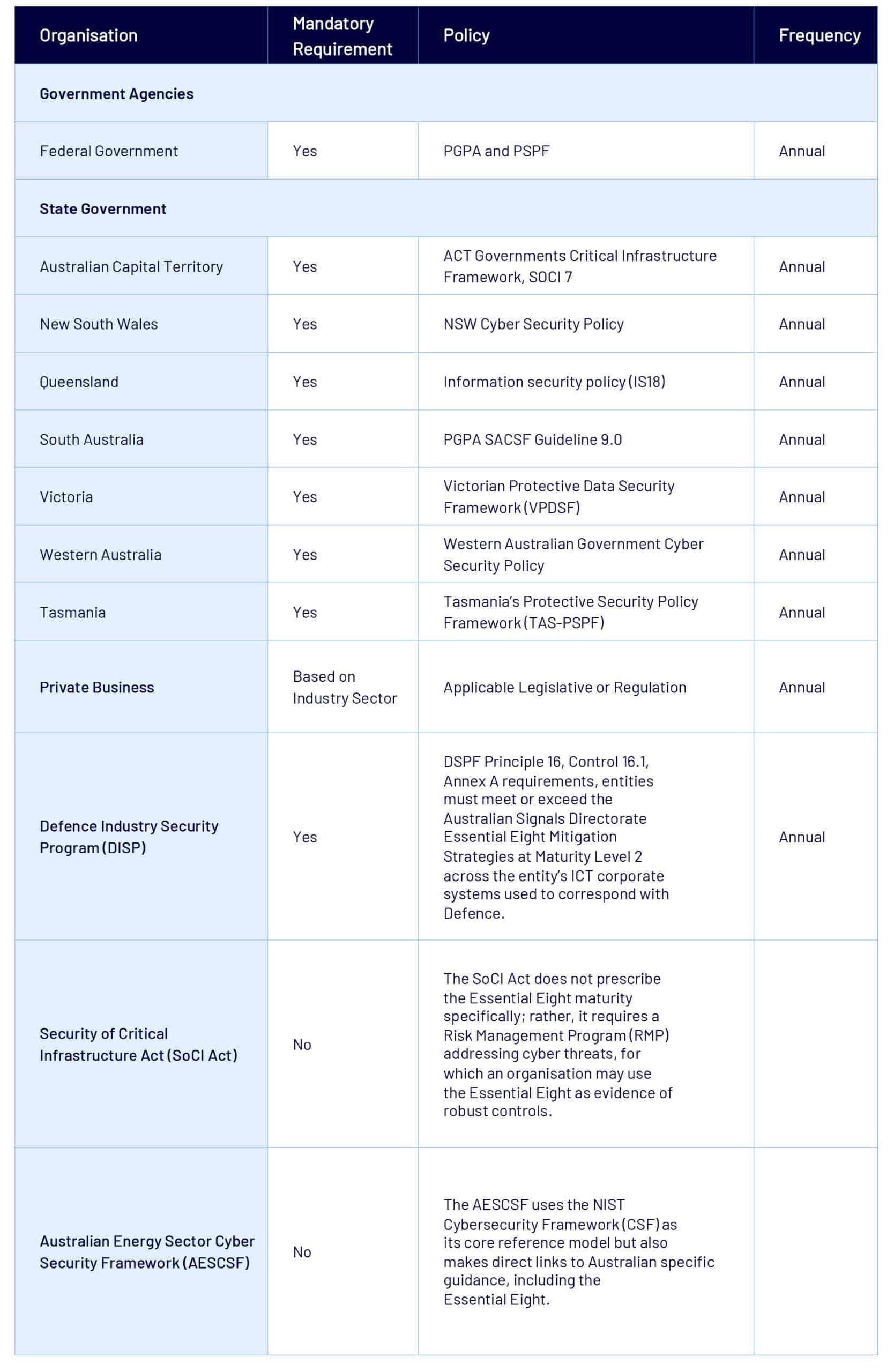

Federal Government

The Directive on the Security of Government Business establishes the Protective Security Policy Framework (PSPF) as Australian Government policy. This means that non-corporate Commonwealth entities subject to the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Act 2013 (PGPA Act) must apply the PSPF (to the extent consistent with legislation).

The PSPF represents better practice for corporate Commonwealth entities and wholly-owned Commonwealth companies under the PGPA Act. Non-government organisations which access security classified information may need to enter into a deed or agreement to apply relevant parts of the PSPF to that information.

State and territory government agencies holding or accessing Australian Government security classified information must apply the PSPF to that information, consistent with arrangements agreed between the Commonwealth, states and territories.

State Government

Many state and territory governments either directly reference the Essential Eight or use it in their own protective security frameworks. More information regarding the Essential Eight requirements for each state and territory government is covered in the table below and details can be found on the State Government section of our website.

Private and Public-Sector Organisations (of all sizes)

The ASD’s ACSC explicitly recommends the Essential Eight to all organisations—including large enterprises, small to medium businesses, and not-for-profit entities. While not always mandated in the private sector, legislative and regulatory frameworks lean on the ASD’s ACSC guidance as a “best practice” baseline.

Did you know?

Many small businesses find the Essential Eight controls too daunting to implement with simple setups (single computers). However, the ASD’s ACSC has written guidance called Small Business Cybersecurity; How to keep your small business secure from common cyber security threats. CyberCX believes in securing our communities across all organisation sizes and we have experience supporting implementation of this advice.

Critical Infrastructure Operators

Under the Security of Critical Infrastructure Act 2018 (SoCI), entities responsible for critical infrastructure are encouraged (and in some cases effectively required) to demonstrate a robust cyber risk posture—often aligning to or exceeding requirements of the Essential Eight. More information is covered in the table below and can be found on the SoCI section of our website.

Individuals

The Essential Eight has primarily been developed for organisations that manage networks, systems, and data often at scale. Despite this, the control areas such as applying patches, restricting administrative privileges, using multi-factor authentication, and performing backups does benefit individuals. The ASD’s ACSC provides specific information with progressive steps to protecting yourself and family with guides.

Australian Economy Spectrum and Drivers

Australia’s cyber security landscape is characterised by a dynamic interplay between government, industry, and individuals, shaped by legislative, policy, and regulatory forces.

Government plays a leadership role in setting strategic direction, with federal and state bodies influencing sectors across the economy, forming the foundation for cyber security resilience and economic stability.

- Government: Federal Government.

- Legislative: State Government.

- Policy: Defence Industry Security Program.

- Regulatory: Security of Critical Infrastructure Act.

- Industry: Australian Energy Sector Cyber Security Framework.

Essential Eight: Controls/Mitigation Strategies

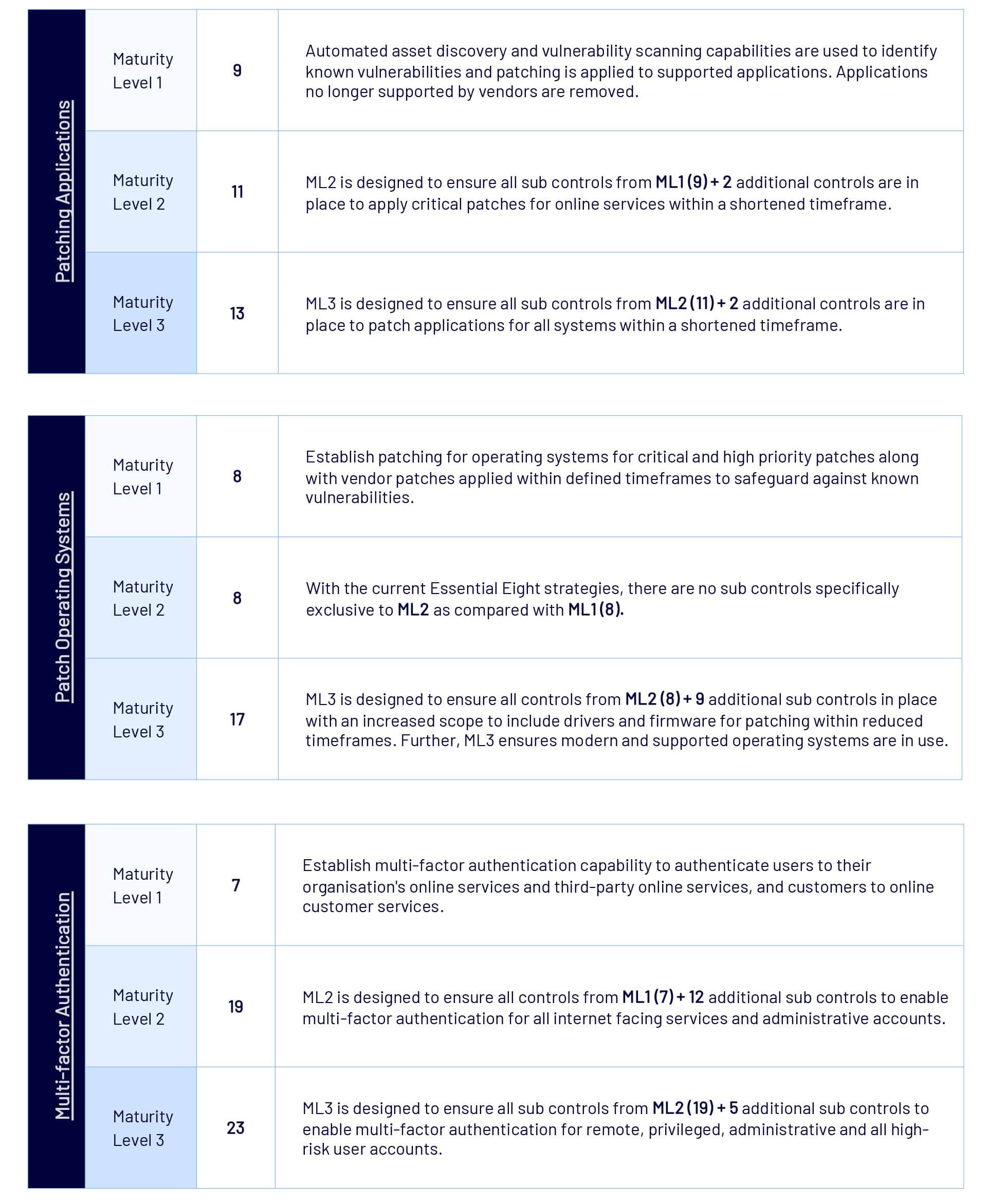

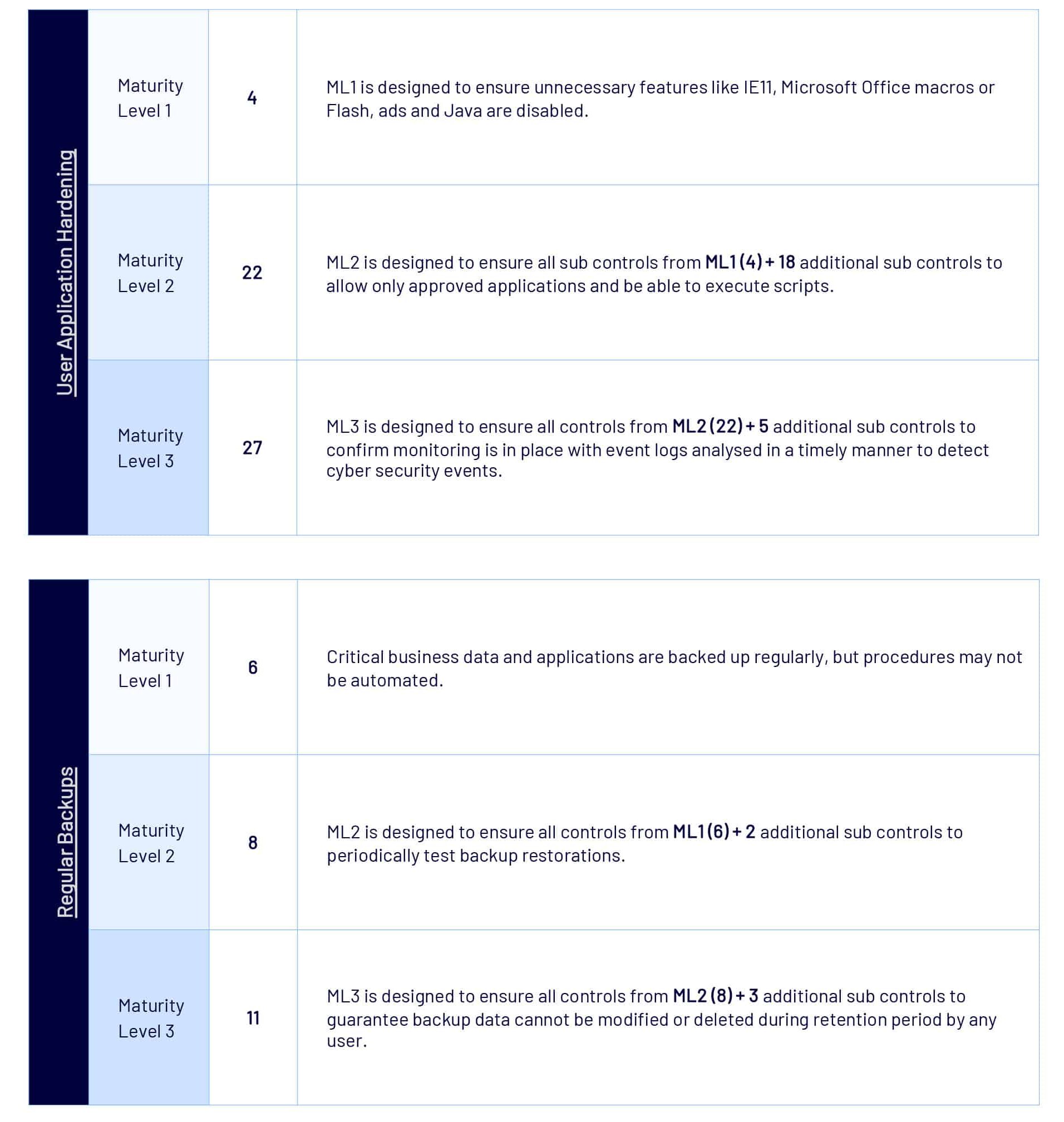

The tables below summarises the intent of the Essential Eight strategies and highlights the number of sub controls per maturity level.

Achieving Optimal Maturity

Patch Applications

Description

Patch Applications refers to the process of updating applications provided by application vendors. These patches often include fixes to security vulnerabilities, bug fixes, and performance improvements.

When a vendor releases a patch for a vulnerability, it should be applied within a timeframe that matches the organisation’s exposure to the vulnerability. For example, once a vulnerability in an online service is made public, it can be expected that malicious code will be developed by malicious actors within 48 hours.

The primary goal of patching applications is to ensure that any known weaknesses in the application are addressed, which in turn helps to protect the system from potential cyber threats and attacks.

At Maturity Level (ML) 1, organisations must use a form of automated asset discovery at least fortnightly. Regular vulnerability scans run daily for online services; and weekly scans for office applications to identify missing patches. Critical patches for vendor mitigations are applied within 48 hours, and noncritical patches within two weeks. Office productivity and related software must be patched within two weeks. Any software no longer supported by vendors is removed to eliminate known vulnerabilities.

At ML2, organisations must add a fortnightly vulnerability scan for all other applications not covered in ML1 and apply patches for those applications within one month of release. All ML1 measures still apply.

At ML3, organisations must accelerate patching even further for office productivity suites, web browsers, email clients, PDF software, and security products, applying critical patches within 48 hours if a working exploit exists or within two weeks if non-critical. Additionally, all other applications not listed above must be removed if they are no longer supported by the vendor. All ML1 and ML2 measures still apply.

Common ways Addressed

- Threat intelligence and vulnerability notification feeds are leveraged to identify vulnerabilities or weaknesses which need to be triaged.

- Organisations make an informed decision about what they are and are not going to patch.

- Triage processes consider the extent of exploitability and existence of known exploits to prioritise patching timeframes.

- Automated patching is enabled where possible.

- Third-party patch management software is deployed to greater visibility and management of application patching.

Patch Operating Systems

Description

Patching Operating Systems promptly reduces the potential for systems to be successfully exploited. This should be focused on internet-facing systems as they are often a target for internet-based threats; however, processes should be applied consistently across the organisation wherever possible.

At ML1, organisations must implement automated methods to identify and patch vulnerabilities in operating systems. This includes regular scans to detect missing patches and applying critical patches promptly. Non-critical patches should also be applied within a reasonable timeframe to ensure systems remain secure. Unsupported software must be removed to eliminate potential vulnerabilities.

There are no controls specifically exclusive to ML2.

At ML3, organisations must use the latest release or the previous release of operating systems and a vulnerability scanner at least fortnightly to identify missing patches or updates for vulnerabilities in drivers and firmware.

Patches, updates, or other vendor mitigations must be applied in operating systems of workstations, non-internet facing servers, and network devices within 48 hours of release when vulnerabilities are assessed as critical by vendors or when working exploits exist. This extends to drivers and firmware across all devices.

If the vulnerabilities are assessed as non-critical by vendors, or no working exploit exists, patches must be applied within one month of release. All ML1 and ML2 measures still apply at ML3.

Common ways Addressed

- Threat intelligence and vulnerability notification feeds are leveraged to identify vulnerabilities or weaknesses which need to be triaged.

- Windows Server Update Services (WSUS) manages patching Windows systems.

- Manual processes are established to patch systems which are not covered by automated tooling (certain Linux systems, or infrastructure devices).

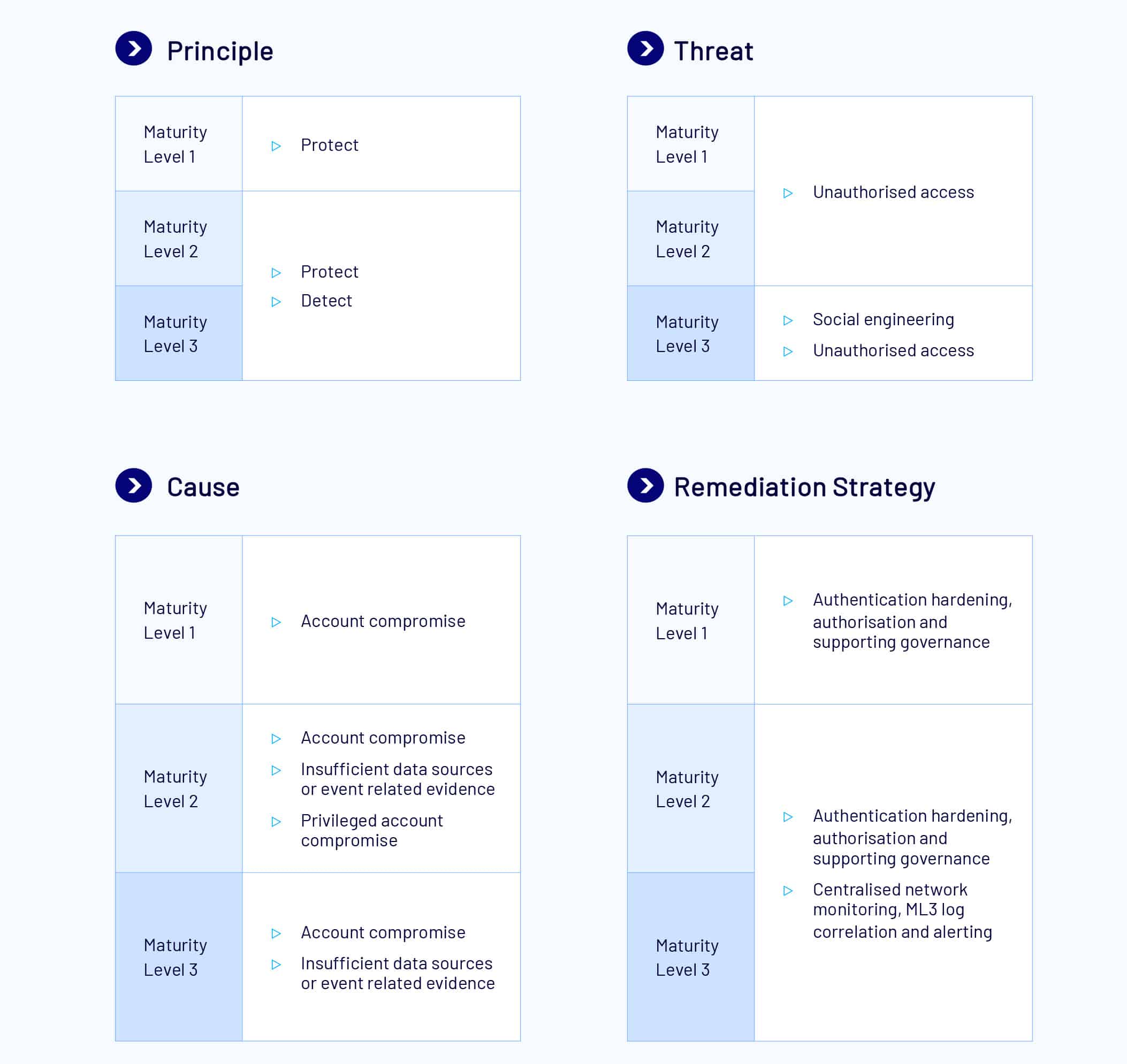

Multi-factor Authentication

Description

Multi-factor authentication (MFA) is one of the most effective controls an organisation can implement to prevent an adversary from gaining access to a device or network and accessing sensitive information. When implemented correctly, multi-factor authentication can make it significantly more difficult for an adversary to steal legitimate credentials to facilitate further malicious activities on a network.

MFA should be implemented for remote access solutions; users performing privileged actions; and users accessing important data repositories which have sensitive or high availability requirements. Using MFA provides a secure authentication mechanism that is not as susceptible to brute force attacks as compared to traditional single-factor authentication methods using passwords or passphrases. MFA factors must include two or more of the following: something users know (i.e. memorised secrets), something users have (i.e. smart cards), or something users are (i.e. biometrics).

At ML1, MFA is used to authenticate users to their organisation’s online services, that process, store or communicate sensitive data. This is also inclusive of third-party online services for sensitive and non-sensitive data, and customer services for organisations and third parties.

At ML2, privileged users are required to authenticate to privileged systems using MFA. Unprivileged users are required to use MFA to authenticate to unprivileged systems. The solution for MFA must be a phishing resistant solution.

MFA events at the ML2 level must also be centrally logged, with these logs being protected against any unauthorised modifications. The logs for MFA must be analysed in a timely manner, to ensure any cyber security events and incidents can be responded to and reported appropriately. All ML1 measures still apply at ML2.

At ML3, MFA is used to access data repositories and must be phishing resistant. Where MFA is applied to accessing customer online services, this also must be phishing resistant. All ML1 and ML2 measures still apply at ML3.

Common ways Addressed

- Microsoft E365 + Federated Authentication (for SaaS).

- Manually configuring individual SaaS solutions.

- Windows Hello.

- Third party digital and physical tokens.

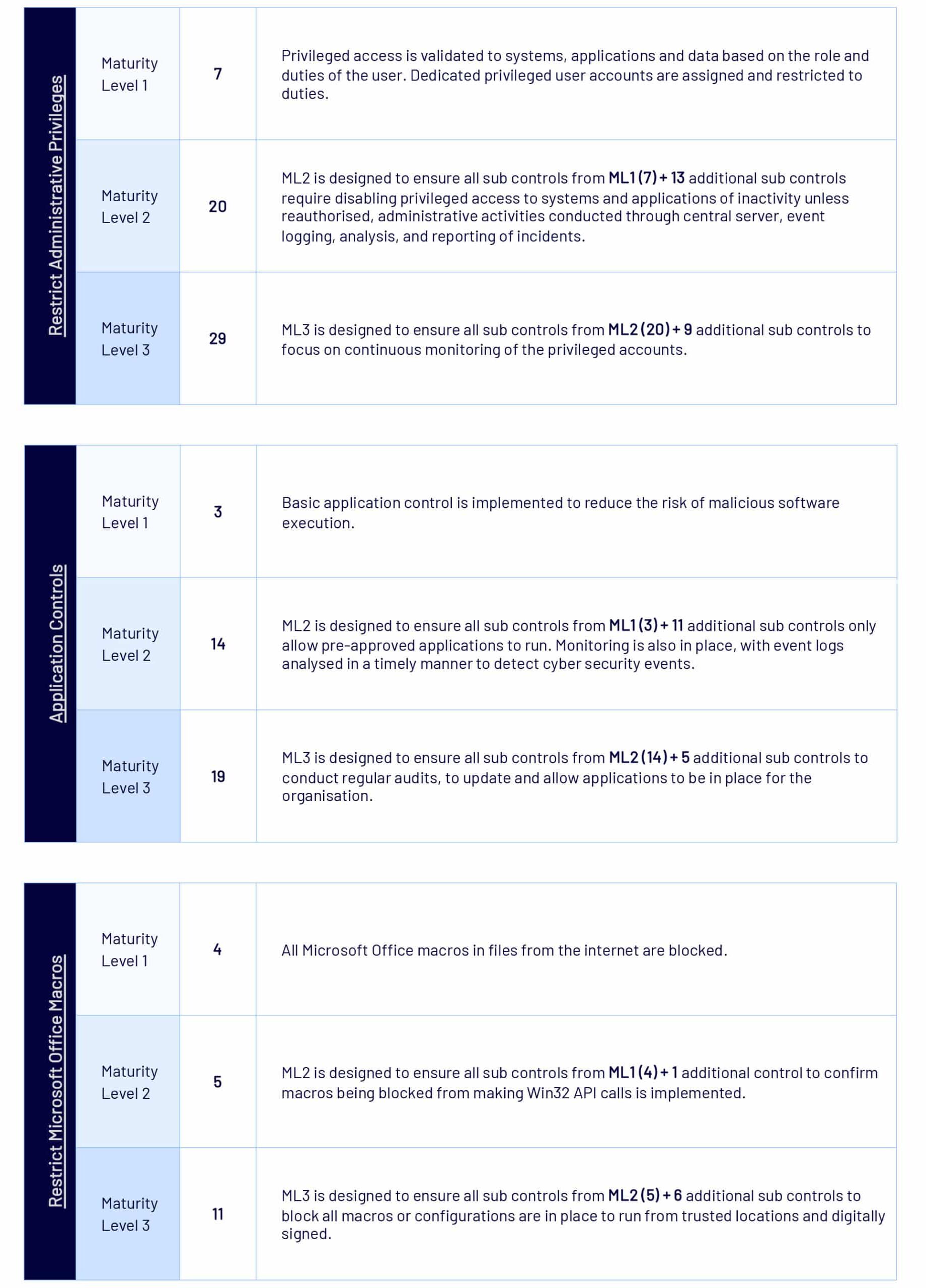

Restrict Administrative Privileges

Description

Restricting administrative privileges is one of the most effective mitigation strategies in ensuring the security of systems. Users with administrative privileges for operating systems and applications can make significant changes to their configuration and operation, bypass critical security settings and access sensitive information.

At ML1, organisations must validate requests for privileged access (upon initial request) and conduct privileged duties via dedicated privileged user accounts. Privileged users are restricted from accessing online services (unless explicitly authorised). Privileged and unprivileged operating environments are restricted to corresponding account types (privileged or unprivileged users, and local administrator accounts).

At ML2, organisations disable privileged access after 12 months (unless validated) or 45 days (if inactive). Privileged activities must be conducted through jump servers and privileged accounts must be appropriately managed, including the enforcement of complex passwords. Virtualisation of operating environments is restricted according to their privilege level. Privileged access and internet-facing servers are logged, protected from unauthorised access or modification, and analysed in a timely matter. Cyber security events are analysed and reported to relevant stakeholders in a timely manner, with the cyber security incident response plan activated as necessary. All ML1 measures still apply at ML2.

At ML3, organisations will strictly limit privileged access to necessity, use Just- In-Time administration (JIT) and administrative activities are conducted through secure admin workstations. Memory integrity, local security authority protections, credential guard, and remote credential guard are all enabled.

Event logs from non-internet-facing servers and workstations are analysed in a timely manner to detect cyber events. All ML1 and ML2 measures still apply at ML3.

Common ways Addressed

- Provision of Role Based Access Control (RBAC).

- Implement Privileged Identity Management and Privileged Access Management.

- Separate accounts used for privileged and unprivileged operations.

- Implement multi-factor authentication.

- Perform regular audits of access logs and permissions granted to personnel.

- Limit internet access possible by privileged accounts.

- Implement User Account Control (UAC).

- Restrict administrative tools such as command line and script execution.

- Provision monitoring and logging of administrative activities.

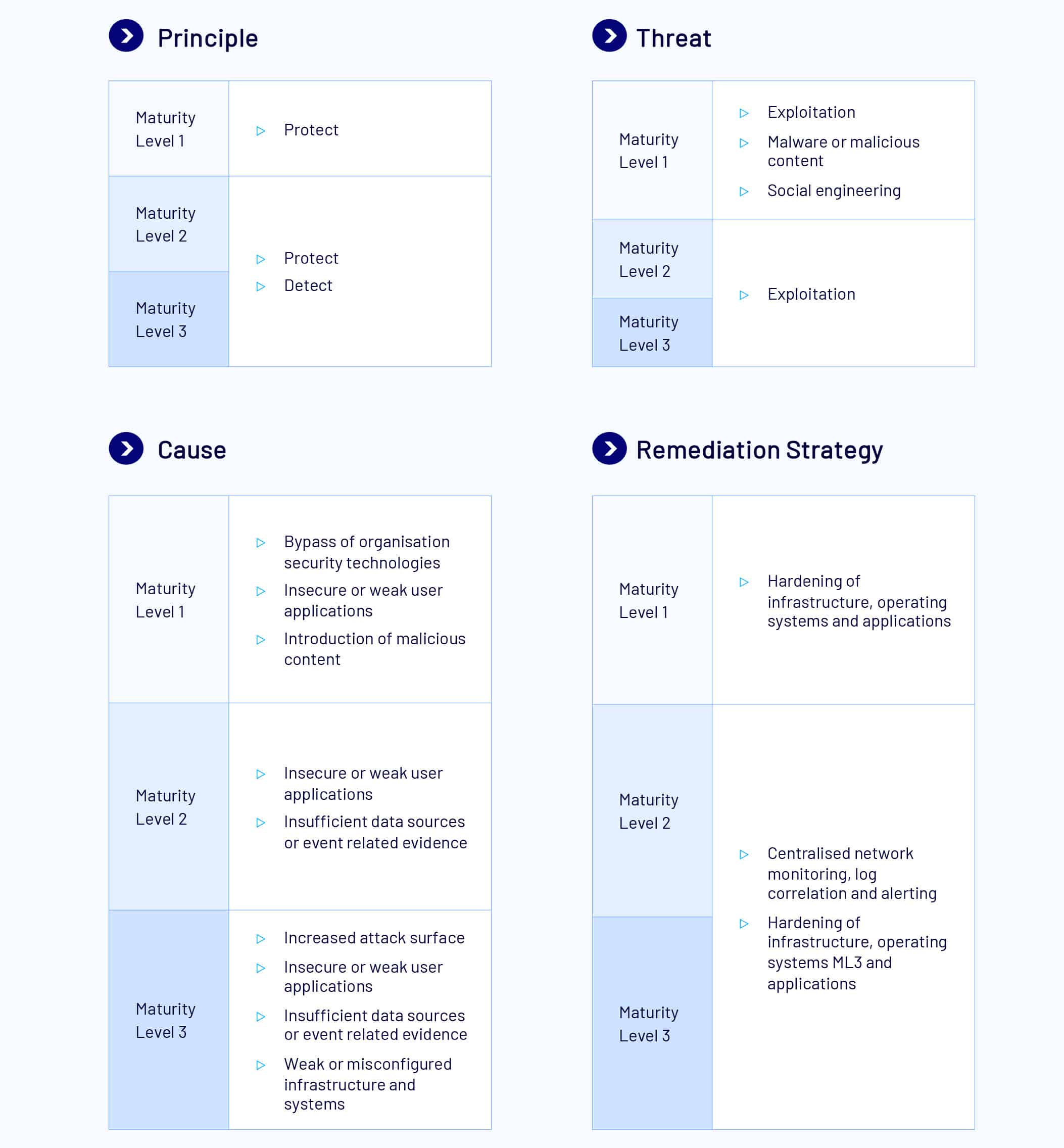

Application Control

Description

Application control aims to prevent the execution of unknown, unwanted, or unapproved executable content on a system, be it a server or an end-user device.

The following approaches are not considered to be application control:

- Providing a portal or other means of installation for approved applications.

- Using web or email content filters to prevent users from downloading applications from the internet.

- Checking the reputation of an application using a cloud-based service before it is executed.

- Using a next-generation firewall to identify whether network traffic is generated by an approved application.

At ML1 application control (app control) is implemented to all workstations of an organisation. It is applied to user profiles used and temporary (temp) folders by operating systems, web browsers and email clients. App control is used to restrict the execution of executable files, software libraries, scripts, installers, complied HTML, HTML applications and control panel applets to an organisation’s approved set of applications.

At ML2, app control is further applied to all internet-facing servers and all locations beyond user profiles and temp folders. Microsoft’s application blocklist must be implemented and all application control rulesets are validated on an annual or more frequent basis. When applications trigger allow and block list events, these events must be centrally logged, securely protected, and analysed in a timely manner.

This is to ensure that any application control cyber security events or incidents can be responded to and reported appropriately. All ML1 measures still apply at ML2.

At ML3, app control is applied on all non-internet facing servers. App control restricts the execution of drivers to an organisation approved set. All of Microsoft’s vulnerable driver blocklist must be applied. Event logs are to include all non-internet-facing servers and workstations, in which these are to be analysed in a timely manner. All ML1 and ML2 measures still apply at ML3.

Common ways Addressed

Application control is often achieved through configuration of features, or the purchase of additional software. These solutions can configure cryptographic hash; publisher certificate or path rules that explicitly block or allow application execution. User education and training with an emphasis on the importance of application control and avoiding the use of unapproved applications can also assist. Examples of solutions can be found below:

- Microsoft AppLocker / Windows Defender Application Control.

- Third party vendor solutions.

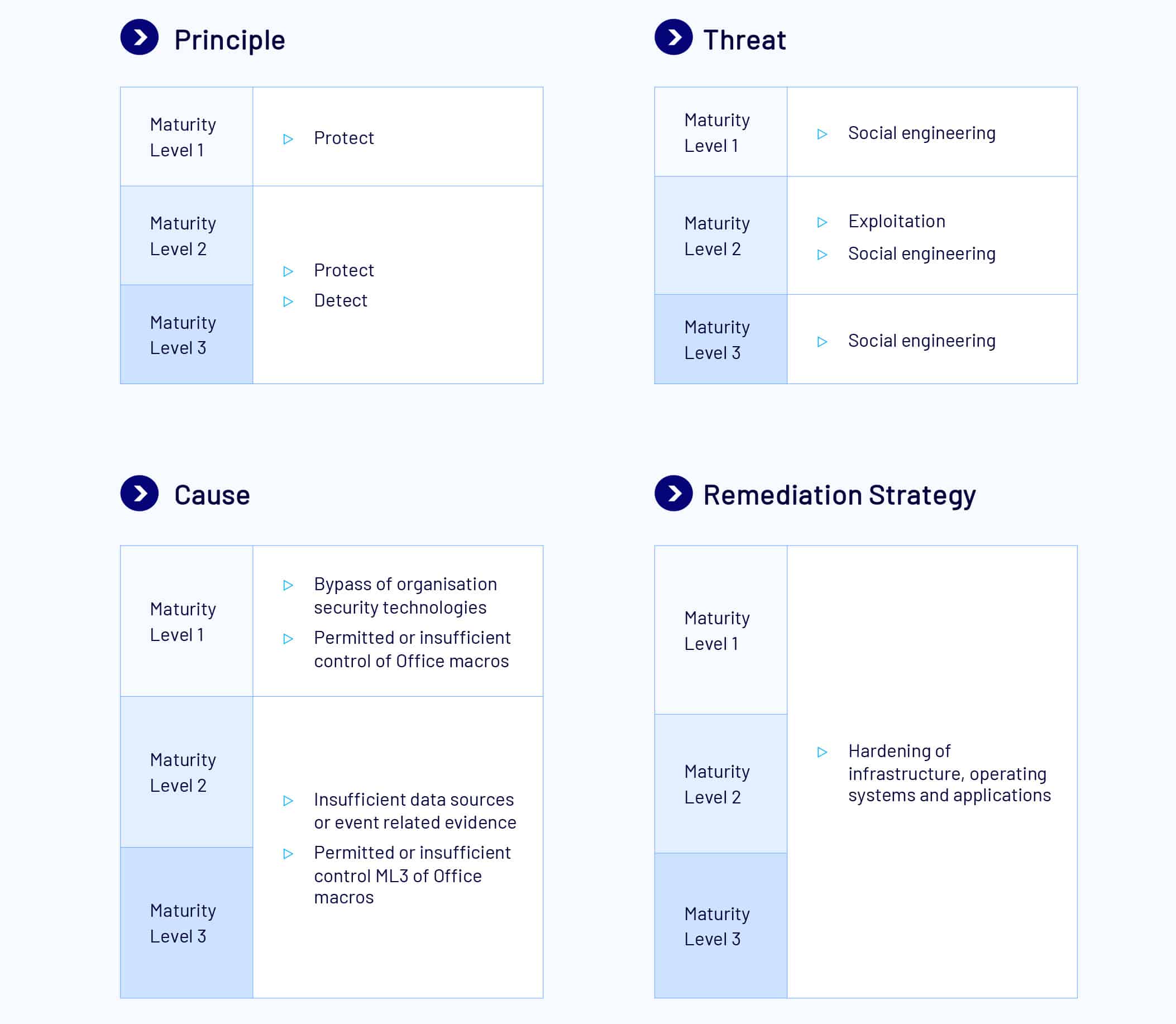

Restrict Microsoft Office Macro

Description

Microsoft Office applications can execute macros to automate routine tasks. However, macros can contain malicious code resulting in unauthorised access to sensitive information as part of a targeted cyber intrusion.

An increasing number of attempts to compromise organisations using malicious macros have been observed. Adversaries have been observed using social engineering techniques to entice users into executing malicious macros in Microsoft Office files. The purpose of these malicious macros can range from cybercrime to more sophisticated exploitation attempts.

At ML1, Microsoft Office macros are disabled for users that do not have a demonstrated business requirement. In addition, macros in files originating from the internet are blocked and antivirus scanning for macros is enabled.

At ML2, Microsoft Office macros are blocked from making Win32 API calls. All ML1 measures still apply at ML2.

At ML3, only Microsoft Office macros running from within a sandboxed environment, a Trusted Location, or that are digitally signed by a trusted publisher are allowed to execute. Macros are checked to ensure they are free of malicious code before being digitally signed or placed within Trusted Locations and only the privileged users responsible for this can write or modify content within Trusted Locations.

Microsoft Office macros digitally signed by an untrusted publisher, or signed by a signature other than a V3 signature cannot be enabled via the Message Bar or Backstage View. V3 is required as Visual Basic for Applications (VBA) macro project signing is a known vulnerability. Microsoft has provided V3 as a secure alternative. Microsoft Office’s list of trusted publishers is validated on an annual or more frequent basis. All ML1 and ML2 measures still apply at ML3.

Common ways Addressed

- Disabling office macros.

- Establishing a group of users who are permitted to leverage macros.

- Blocking macros inbound via content filters.

- Creating a trusted location for approved macro storage and execution.

- Ensuring all macros are analysed in a sandbox environment for any malicious content.

- Ensuring all macros are digitally signed.

User Application Hardening

Description

Workstations are often targeted by adversaries using malicious websites, emails or removable media in an attempt to extract sensitive information. Hardening applications on workstations is an important part of reducing this risk.

At ML1, web browsers do not process web advertisements or Java from the internet; Internet Explorer 11 is disabled; and web browser security settings cannot be changed by users.

At ML2, web browsers, Microsoft Office productivity suites, and PDF software are hardened using ASD and vendor hardening guidance, with the most restrictive guidance taking precedence when conflicts occur. Microsoft Office productivity suites are blocked from creating child processes or executable content, injecting code, and object linking and embedding packages. PDF software is prevented from creating child processes. Users are prevented from changing security settings for Office productivity suites and PDF software.

PowerShell module logging; script block logging; transcription events; and other command line process creation events are centrally logged.

Event logs are protected from unauthorised modification and deletion. In the case of internet-facing servers, event logs are analysed in a timely manner to detect cyber security events.

Cyber security events are analysed in a timely manner to detect cyber security incidents. Cyber security incidents must prompt the enactment of an incident response plan; are reported to the ASD and to the Chief Information Security Officer (CISO), or one of their delegates as soon as possible after they are discovered. All ML1 measures still apply at ML2.

At ML3, event logs for workstations and non-internet facing servers are analysed in a timely manner to detect cyber security events. PowerShell is configured to use Constrained Language Mode. Windows Powershell 2.0 and .NET Frameworks 2.0; 3.0; and 3.5 are removed. All ML1 and ML2 measures still apply at ML3.

Common ways Addressed

- Microsoft Intune configuration.

- Group Policy.

- Following vendor or authority hardening guidance for the configuration of web browsers; PDF software and security products.

Regular Backups

Description

Regular backups refer to the practice of creating and maintaining copies of critical data, systems, and applications, to ensure information can be restored in the event of data loss, corruption, or a cyber security incident.

By implementing regular backups, organisations can minimise the impact of data loss or corruption and ensure business continuity in the face of cyber security incidents or other disruptions.

At ML1, backups of data, applications and settings are performed and retained in accordance with business criticality and business continuity requirements. These backups are to be synchronised to enable restoration to a common point in time. This common point in time is to be tested as part of disaster recovery exercises. These backups must be retained in a secure and resilient manner. Unprivileged users cannot access backups other than their own and are also restricted from being able to modify and delete these backups.

At ML2, privileged users cannot access backups other than their own, except for backup administrators. Privileged users are also prevented from modifying and deleting these backups. All ML1 measures still apply at ML2.

At the ML3 level, privileged and unprivileged users are denied from accessing their own backups. Backup administrators are also prevented from modifying and deleting backups during their retention period. All ML1 and ML2 measures still apply at ML3.

Common ways Addressed

- Automated backup solutions.

- Offsite storage.

- Encryption.

- Regular testing.

- Versioning.

- Access controls.

- Documentation and policies.

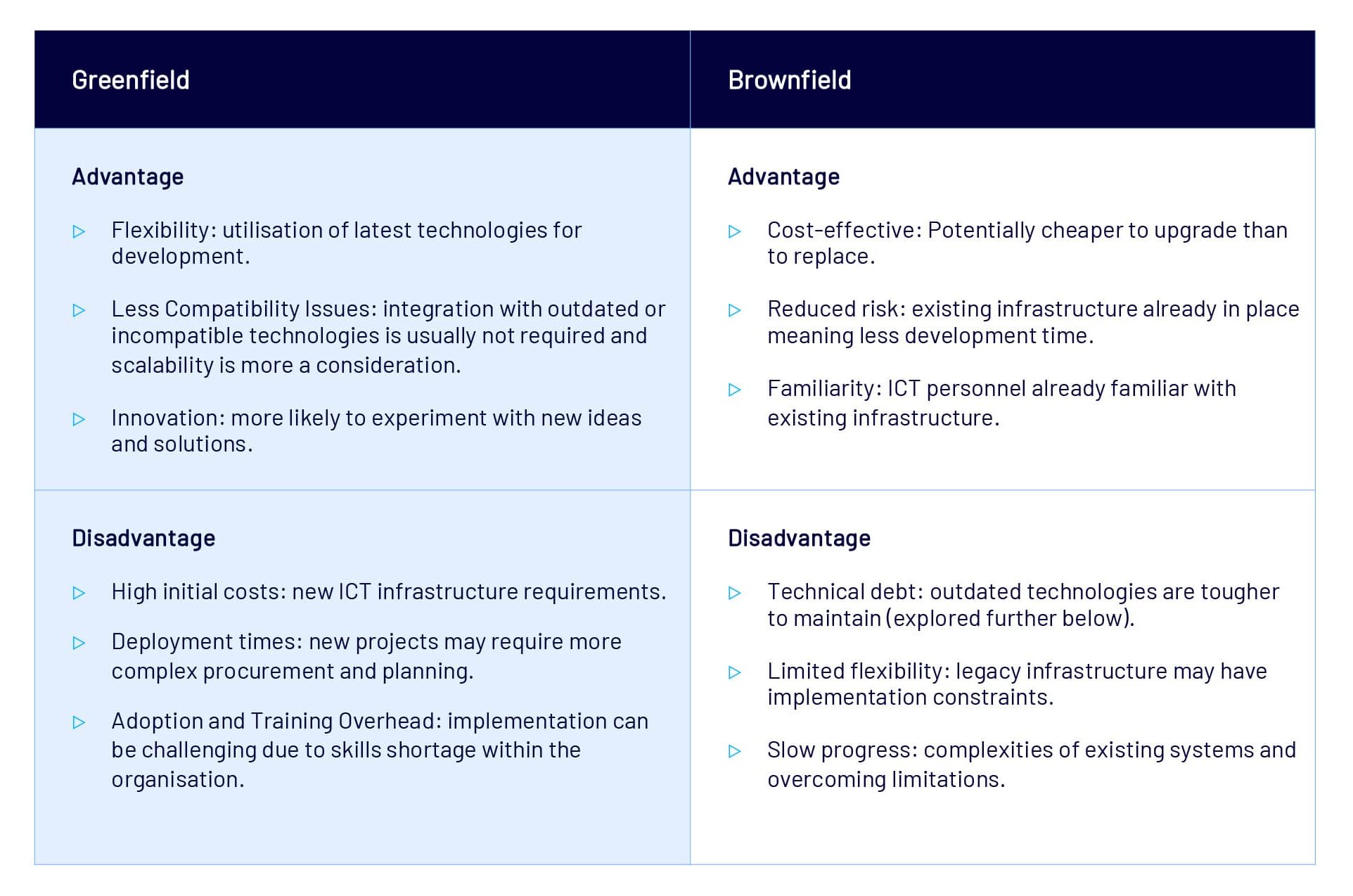

Improving Security – Greenfield vs Brownfield

In Information and Communication Technology (ICT), Greenfield and Brownfield refer to approaches to system implementation.

Both approaches have strengths and weaknesses from an information security perspective.

A “greenfield” project starts from scratch, in an undeveloped environment that is not constrained by legacy technology. The ICT design and build process can be fully innovative by not using existing systems, architecture, or code base to integrate or replace.

There is flexibility to adopt the latest best practices, frameworks, or tools without dealing with backward compatibility. Often leading to faster initial development with less hurdles of legacy data, code, or processes.

A “brownfield” project occurs in an active environment, where existing systems are already in place. Often organisations need to navigate legacy integration with existing systems, data, or processes. Incremental changes are common to iteratively improve or phase out components gradually, rather than starting completely afresh.

Constraints with deployments can often lead to the potential for technical debt and can carry forward vulnerabilities in legacy technologies. These vulnerabilities can necessitate additional mitigation strategies being required, further increasing complexity and potential attack surface.

The table below highlights some of the typical advantages and disadvantages of both greenfield and brownfield projects:

Technical Debt

Brownfield projects generally involve modernising existing technical infrastructure.

Although this can be cost-effective and may carry lower upfront risks, organisations often accumulate technical debt when legacy systems cannot be fully decommissioned.

By retaining superseded or incompatible technologies, projects can progress more quickly, but this approach requires ongoing monitoring and remediation. If technical debt is allowed to accumulate, outdated systems become increasingly vulnerable to exploitation, making timely updates and proactive security measures essential to maintain a robust and secure environment.

To move forward effectively, teams should triage technical debt items by identifying the most critical operational and security risks first.

This approach ensures ‘quick wins’ and early impact, while systematically mitigating vulnerabilities inherent in outdated components.

By focusing resources on the biggest threats, organisations can steadily modernise legacy systems without halting daily operations, ultimately achieving a more stable, secure, and future-ready environment.

TIP: Proactive vulnerability scanning across environments can help identify vulnerabilities in systems and programs allowing proactive triage. Vulnerability scanning tools can be executed in your environment or penetration testing can be performed against the system or program. The CyberCX Complete Guide to Security Testing Assurance is a detailed guide on the types of activities that can assist with vulnerability identification.

Effective management of technical debt is often achieved through a Plan of Actions and Milestones (PoAM). The PoAM is typically designed to assist organisations in tracking and managing remediations identified as a result of a security assessment. Typically, a PoAM includes:

- Actions

- Milestones

- Responsibilities

- Priority

- Status

- Start and finish dates

Structuring a timeline and accountability framework in brownfield and greenfield projects helps address both technical debt and modernisation goals, significantly increasing the chances of success by providing clarity, focus, and alignment to all stakeholders in projects.

Managing technical debt from the outset and defining modernisation goals helps teams ensure their efforts align with project initiatives, avoid scope creep and wholistically improve alignment with organisational objectives. By setting a PoAM, an accountability framework is established, providing transparency within teams regarding assigned roles and responsibilities, fostering a culture of collaboration, responsibility and increasing the likelihood of a project’s success.

The Essential Eight and Managing Technical Debt

Choosing greenfields or brownfields system implementation can have a significant impact on security complexity, including achievement of Essential Eight maturity.

Once an organisation has identified its legislative, policy, and regulatory obligations and chooses a target Essential Eight maturity level, it may need to conduct a cost analysis to decide whether to modernise its existing (brownfield) environment or adopt a completely new (greenfield) approach.

CyberCX will often see established organisations with complex on-premises and cloud systems retrofit or integrate the Essential Eight strategies into their already-running environment. Typically, we will see the greenfield approach for brand-new companies and startups, as they can embed the Essential Eight mitigation strategies from day one.

How can CyberCX help?

CyberCX provides end-to-end cyber capabilities and can assist with your implementation and assessment journey when aligning to the Essential Eight. Learn more about our Essential Eight services.

Greenfields – Nebula

A common issue with the current deployment of hyperscale cloud services designed for public use is that it often fails to meet the requirements of organisations handling highly sensitive workloads.

Insight

If you are establishing a particular program or project that requires a high Essential Eight Maturity Level, consideration to standing up a new hardened environment should be given.

CyberCX in collaboration with Curtin University have launched a secure sovereign cloud service called Nebula, providing users the ability to develop and store research-related files safely away from everyday files, including sensitive data sets, research papers and other key documents.

The Nebula environment is designed to meet the ISM’s PROTECTED standard and can be deployed by CyberCX’s specialised team within weeks, utilising AI, seamless collaboration, and ongoing security improvements to meet industry and government requirements.

CyberCX has deployed Nebula utilising the greenfield project approach to industries including defence, defence industry providers, federal government, financial institutions, health, mining, education (with a focus on research) and commercial organisations that require secure environments.

CyberCX’s Governance, Risk and Compliance team strive to ensure that Nebula, a multi-tenanted cloud platform, is continually aligned with ongoing updates to ASD’s Essential Eight framework at the ISM PROTECTED level.

CyberCX understands the importance of an organisation’s ICT infrastructure development and aims to provide guidance on IT infrastructure advancement.

Glossary of Terms

Cyber event or Incident

The threat of a cyber event or incident is concerned with the identification, response, and management of the event. Specific events may be any form of threat to the system; however, a failure to suitably manage these events will result in increased likelihood of severe impacts occurring.

Data Spill

A data spill threat specifically relates to an often unintentional information disclosure where classified information is mishandled, either being processed or connected to a system that is not authorised to handle the information or sensitivity/classification.

Data Sovereignty

Data sovereignty threats differ depending on the context of the information system. These are typically concerned with information disclosure or tampering by malicious external parties, such as FIS; however, can present legal issues depending on relevant legislation.

Eavesdropping

Eavesdropping is the interception (information disclosure) of audio information by a threat actor. This may be overhearing a sensitive or classified conversation either within a natural environment, or through the installation or abuse of system functionality such as telephones or microphones.

Exfiltration

Exfiltration (information disclosure) is the action of extracting information from an information system. This may be through physical or electronic means potentially via overt methods, or by abusing functionality in a covert way.

Exploitation

Exploitation is the action of intentionally taking advantage of a weakness or vulnerability in an information system for the advantage of a threat actor, to perform actions which are either not permitted or authorised.

For additional context, this is an umbrella term to take advantage of systems or software in a malicious manner.

This may be as part of an attack chain, where exploitation of low level systems enables a threat actor to position themselves to execute their goal, such as stealing information.

Mitigating controls for exploitation threats are general hardening, and prevent common types of attacks, but are not specifically targeted to reduce the impact of specific threats (such as exfiltration, etc.).

False sense of security

A false sense of security contributes to mismanagement, either through misreporting, misrepresentation of risks or information, or by having a warped perception of the security posture of the environment.

Incompetence

Incompetence is a user’s ability to do something successfully, usually related to their level of awareness or training. Incompetence is always and entirely a personnel and training issue that can be managed, but without this, users may unintentionally expose the system to significant risk.

Information loss or disclosure

Information Loss or Disclosure may be the goal of an attacker, or it may be an occurrence due to an accidental incident such as losing a mobile device.

Such a threat occurs when information associated with a system becomes uncontrolled and must be treated as disclosed. Examples include data breaches, lost devices, unauthorised access to sensitive information or actions such as forwarding emails to unauthorised parties.

Insecure development

An action which may see the introduction of vulnerabilities or weaknesses into an application or system.

Irresponsible disclosure

A specific form of information disclosure related to poor handling of security notifications by external parties, such as security researchers. In the event notification is received of an issue, the potential for the vulnerability or weakness to be published exists where notification is not handled in due time with due care.

Lateral movement

Lateral movement threats occur because a threat actor has a form of access to an initial system, and a desirable target system.

Threat actors may leverage access they have obtained as a stepping stone to pivot into other areas of the information system either horizontally or vertically when combined with privileged escalation.

Lateral movement is the action occurring when an attacker “moves throughout a network”.

Litigation

Litigation is a threat to a business which may present itself due to decisions made associated with an information system. These should be suitably considered in order to protect the interests of the company while ensuring no breach of associated legislation occurs.

Loss or Theft

A physical attack against a system asset which introduces a means for information disclosure, tampering or exploitation by malicious actors with an opportunity to obtain equipment or information associated with an information system.

Malware or malicious content

Malware or malicious content is software which can cause due harm to an information system.

Viruses, worms, trojan horses or ransomware all have the potential to cause a significant impact to an overall information system if they are introduced and executed.

Malware or malicious content may be introduced into an information system through various means; however, the delivery is often considered as part of alternate threats, and the goal of protecting against malware is to detect it in the event is is able to transfer or begin transferring into the system.

Microsoft Office Macro

Office Macros allow users to automate repetitive tasks and integrate logic to support the creation and management of documents. Their issue is that they can be used by threat actors to include malicious code that can be executed when opened.

Mismanagement

Mismanagement as a threat to an information system relates to the overarching governance and management of that system which if poor or of low maturity, often results in a decreasing security posture over time, increasing the likelihood of compromise.

Misuse of services

Often unintentional but not exclusively limited to, users may leverage services because they’re accessible without understanding the associate impact of their actions.

This can include excessive private usage of system, accessing illicit, explicit or potentially dangerous content, or otherwise unintentional consumption of resources.

Multi-Factor Authentication (2FA)

MFA is a security measure that requires more than one way to verify identification before accessing information.

This can include authentication a combination of something the user knows (password, pin, etc) , something the user has (security card, smart token, etc), and something that is part of the user (biometrics).

Personnel safety

A threat to a person’s life.

Privilege abuse

Privilege abuse occurs when a user with significant or excessive privileges takes advantage of this situation to execute actions of negative consequences.

While technically authorised such actions would not be considered permitted and may include bypassing necessary processes or ignoring separation of duty requirements.

Reconnaissance

Reconnaissance actions are those executed to obtain information about a potential target.

While usually non-invasive, taking actions to prevent these threats can increase the time sink required to develop attack strategies, and may force a threat actor to leverage invasive information gathering means.

Repudiation

Repudiation occurs when a user can reasonably deny actions taken, as there is insufficient evident or information to associate their person with actions taken. This presents significant complications during incident response and forensic investigation.

Service disruption

An event which occurs which results in services associated with the system becoming unavailable, or otherwise impacted. This can include failures, denial of service attacks or excessive resource consumption.

Signal emanation

Electrical signals generated from standard systems, or intentional emanations from RF equipment introduce a means of information disclosure or tampering by malicious actors within physical proximity.

Social engineering

Malicious activities which are accomplished through human interactions, leveraging psychological manipulation to trick users to action a task achieving the goal of a threat actor.

This may be a vector leveraged to achieve threats against the system (i.e disclosure, tampering, unauthorised access, malware, etc.)

Supply-chain attack

Malicious activities which are accomplished through human interactions, leveraging psychological manipulation to trick users to action a task achieving the goal of a threat actor.

This may be a vector leveraged to achieve threats against the system (i.e disclosure, tampering, unauthorised access, malware, etc.)

Tampering

The modification or alteration of equipment or information whereby the asset’s integrity is compromised.

This may be to introduce an exploitable vulnerability or configuration or modify equipment or information to achieve an objective.

Unauthorised access

The action of a person who has not be provided with appropriate authorisation (either formally, or technically via a system) performing a task, or attempting to, for which they do not have permission (need to know, need to access).

Case Studies

Case Study 1: Government Agency

Context

A prominent government agency found itself grappling with mounting cyber threats and regulatory requirements, realising that dated patching practices and potential vulnerabilities could significantly compromise its environment. Determined to bolster its security posture and meet the Essential Eight Maturity Level 2 as per their regulatory requirement, the agency needed a thorough vulnerability and patch management assessment to pinpoint and address its most critical gaps. trusted partner to achieve the mission.

Our Solution

CyberCX conducted a detailed review of the client’s environment alongside mapping the stakeholder landscape engaged and involved in the journey. The mobilised team mapped vulnerabilities and status of patch management maturity levels across all high priority assets. In-depth analysis combined with industry experience, the team highlighted the client’s highest risk areas and identified the most pressing gaps in their security posture. Building on the findings, CyberCX developed a comprehensive prioritised roadmap that addressed immediate risks, adopted industry best practices and established a phased plan to achieve Essential Eight Maturity Level 2 alignment over two years. This roadmap was carefully aligned with the client’s broader strategic enterprise goals, ensuring each milestone delivered tangible progress while strengthening their overall cyber resilience.

Outcomes and impact

The vulnerability and patch management review fused system reviews with hands on technical assessments. By exposing key process gaps and shaping a clear, methodical remediation plan, CyberCX helped position the client on a confident trajectory toward enhanced security and alignment. Throughout the venture, the team flexed seamlessly in the face of new demands and fostered a truly collaborative partnership – earning genuine praise for a refined, professional approach. The client highlighted the tangible, long-term value of this engagement and CyberCX as the trusted partner to achieve the mission.

Case Study 2: Travel Industry

Context

As a leading travel industry services provider in Australia, the client recognised the need for a stronger cyber security foundation given the exposure to geopolitical threat landscape. Eager to ensure robust protection for its clients and operations, the client turned to the Essential Eight Framework – an established benchmark for mitigating common cyber risks. With an aim to understand its current state and path forward, the client enlisted CyberCX to conduct an Essential Eight Maturity Assessment at their desired maturity level.

Our Solution

CyberCX’s in depth review and analysis revealed the client’s gaps in comparison to their desired Essential Eight Maturity Level, it had effectively implemented some, but not all the controls examined. The discovered gaps formed a solid starting point for further development. The findings provided the client with a clear view of its strengths and gaps, empowering them to build a targeted roadmap to boost cyber security readiness, enhance risk management and work toward alignment to all domains of the Essential Eight framework.

Outcomes and impact

Through a mix of thorough reviews, gap analysis and strategic recommendations, CyberCX delivered a meaningful roadmap for the client’s cyber uplift journey. By highlighting both what was working and where improvements were needed, CyberCX provided clarity and momentum required to strengthen defences against the most prevalent cyber threats. Confident in its next steps, the client is now better positioned to protect its critical operations and maintain its leadership in Australia’s competitive travel services industry.

Improve your cyber security posture by implementing the Essential Eight with CyberCX

CyberCX is Australia’s leading cyber security provider with unmatched skill and expertise across all areas of the Essential Eight.

Contact us to find out how we can help your organisation’s cyber security posture by adopting the Essential Eight.