Ransomware and Cyber Extortion Guide 2023

How to protect your organisation

This Best Practice Guide provides practical tools for people at all levels of an organisation to understand and manage the risk posed by ransomware and cyber extortion.

Read the guide below, or download the PDF to learn the steps you can take to protect your organisation from ransomware and cyber extortion.

Ransomware and Cyber Extortion Guide contents

Part 1:

Cyber extortion: State of play in 2023

What is cyber extortion and how does it work?

Cyber criminals are using two dominant cyber extortion strategies: ransomware and data theft extortion

In a typical ransomware attack, the attacker disrupts the availability of a victim organisation’s files or systems to impact their operations.

The attacker gains unauthorised access to a victim’s network and runs malicious software known as ‘ransomware’. The ransomware typically encrypts files, making them unreadable. Affected files can include user files such as documents and spreadsheets or system files which are required for computers to properly operate. A significant trend in recent times is the encryption of entire virtual machines.

Some attacks make other changes, such as locking systems to make them inaccessible to users or displaying ‘ransom notes’ on screen to alert users to the attack and instruct them how to pay their attackers. The effects of ransomware can normally be reversed by using a decryption program or key, which the attacker usually promises to provide in exchange for a payment.

Data theft extortion involves the attacker stealing confidential information and threatening to share it in a way that will cause harm to the organisation, or in some cases, individuals whose data has been stolen.

Data theft extortion has become increasingly popular among cyber criminals since late 2019 and has accelerated in popularity in the last two years. It is often (but not always) combined with ransomware – an approach called ‘double extortion’. CyberCX saw double extortion tactics used by cyber criminals in over 70% of the incidents we responded to last year.

Who’s being impacted by ransomware and cyber extortion?

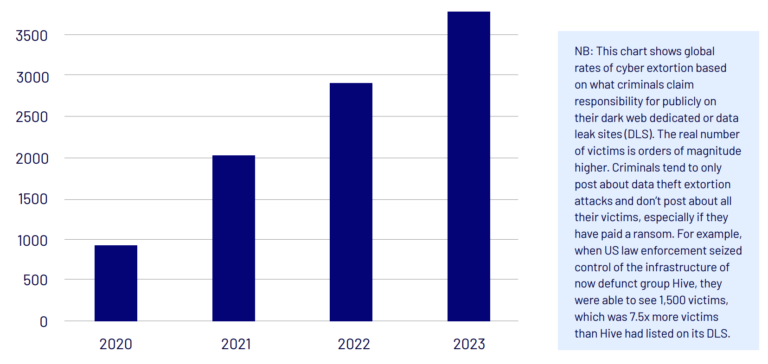

The scale and impact of cyber extortion has increased since 2017, with a sharp uptick in 2021. While there was a lull in attacks in early 2022, likely due to the Russia-Ukraine War, cyber extortion attacks continued to rise across 2022 and 2023.

In 2023, CyberCX Intelligence observed total cyber extortion attacks increase quarter on quarter for the first three quarters of the calendar year. But what we see reflects only a fraction of overall cyber extortion crimes. Many attacks go unreported.

Every organisation, of every size, in every sector, is a potential target.

Attacks against essential services and critical infrastructure providers, government entities and large corporations continue, following the logic of ‘big game hunting’. Under this strategy, attackers target larger organisations, surmising that they may be more willing and able to pay large ransoms.

However, criminals also target smaller organisations. In the last two years, CyberCX has observed a renewed focus by cyber criminals on small to medium sized organisations. This is because the lucrative cyber extortion economy is attracting more and more criminals, while the rise of ransomware-as-a-service has lowered barriers to entry.

Increased public awareness, especially of ransomware, has also meant big organisations with big security budgets are getting better at preparing for and defending against cyber extortion. Cyber criminals who lack the technical sophistication or risk appetite to target bigger organisations aretherefore looking for softer targets further down the food chain.

2020-23: Global attacks claimed by cyber extortion criminals

Source: dark web posts by cyber criminals, scraped and verified by CyberCX Intelligence.

The rise of third-party data breaches One of the key trends we’ve observed since releasing our last Best Practice Guide is the rise of third-party data breaches – which are expanding the ‘blast radius’ of cyber extortion attacks.

Organisations are increasingly being affected by cyber extortion attacks against their supply chain and contractual partners. In the case of ransomware, this can result in the disruption of services provided by third parties. In data theft extortion cases, we have observed a sharp uptick in the number of organisations whose data has been leaked online following a breach of a supplier or partner. Threat actors are also increasingly attempting to extort third- or fourth-party victims, especially where the primary victim’s operations are predominantly B2B rather than B2C. This trend highlights the inherent risk every organisation must understand, assess and manage when engaging third parties who will have some form of access to your systems or data.

In all cases, third-party cyber extortion incidents create additional complexity and pressure, as indirect victims face harm but are not in the driving seat of the incident response. A third-party breach may also result in uncertain legal challenges for your organisation regarding your relationship with the third party, as well as contractual or other obligations you may have with your customers, suppliers and stakeholders.

When victims become pariahs

As the threat of cyber extortion has steadily increased in recent years, CyberCX has observed a steady decline in the risk tolerance of customers and stakeholders of organisations targeted by an attack. As if to add insult to injury during a cyber crisis, a growing number of victims are finding themselves having to spend significant time and effort to assure their stakeholders that they are not in imminent danger of the attack spreading to their systems. This is particularly evident in incidents where the victim has systems or databases connected to their stakeholders for the purpose of providing services or doing business. Stakeholders that disconnect their systems from the victim, whether out of an abundance of caution or a misplaced fear of cross-contamination, can cause further operational disruption to the victim and make remediation more problematic.

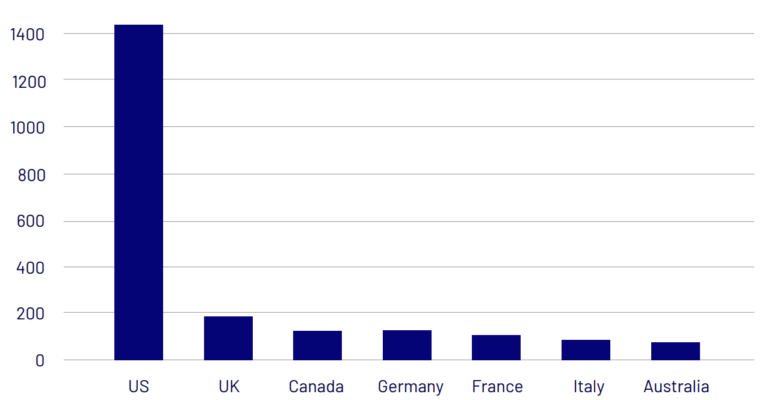

2023: Global cyber extortion incidents by victim location

Source: public declarations by cyber criminals and otherwise publicly reported incidents.

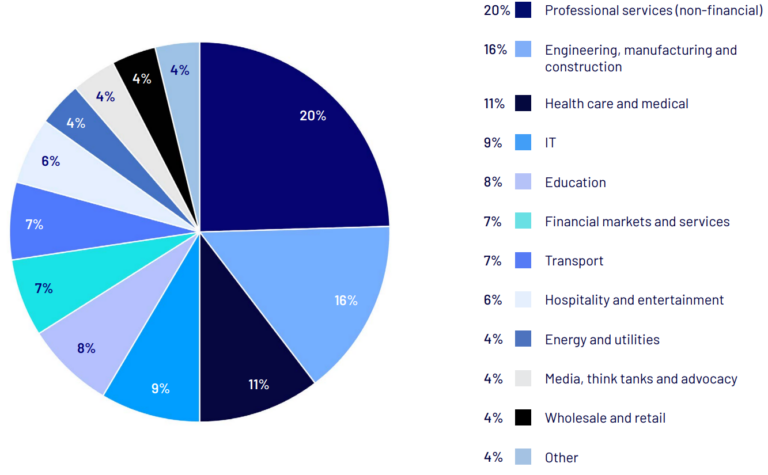

Australia and New Zealand Snapshot: Sectors most affected by cyber extortion

Source: public declarations by cyber criminals and otherwise publicly reported incidents.

Which criminal groups are most active?

Since 2021, we have witnessed the dissolution of some of the more formidable ‘ransomware giants’. Notable big operators like Conti, REvil and Darkside, whose victims included Medibank, JBS, Colonial Pipeline, Acer, the Irish health service and the Costa Rican government, have disbanded due to a variety of reasons, including law enforcement operations, the impacts of the Russia-Ukraine war, and sanctions against entities and payments services. The consequence is a more fractured and diverse cyber extortion ecosystem. Members of disbanded groups have joined other groups, restructured or rebranded.

The cyber extortion economy has also continued to adapt, with a growth of the initial access broker marketplace and of the ransomware-as-a-service business model, driving growth and efficiency. This is compounded by the rise of commodity malware, including information stealing malware, and easily accessible freeware like open-source offensive security tools, evasion tools and Remote Management and Monitoring (RMM) software, collectively lowering the technical barrier to entry for cyber criminals.

How are the criminals breaking in? Changes to initial access markets and methods

Credential theft and initial access

The initial access broker feeder economy has grown. We have noticed a marked increase in the number of incidents where initial access was purchased by a threat actor after legitimate credentials were advertised and sold on the dark web. CyberCX Intelligence is tracking an overall increase in the availability of credentials online, a trend that has coincided with the proliferation of commoditised “information stealing malware”, which enables threat actors to harvest credentials at scale.

Cyber criminals are adapting to best practice defences and using innovative techniques to bypass multi-factor authentication (MFA). For example, the use of phishing pages that overcome MFA through session capture is becoming the norm rather than the exception.

This means that while protecting against phishing emails continues to be best practice, organisations need to take action to minimise the incidence and risk of exposed credentials including, where possible, disconnecting their enterprise attack surface from employee devices and identities, and monitoring for stolen enterprise credentials online.

Social engineering

Newer groups such as Scattered Spider, responsible for the cyber extortion against MGM Resorts, and LAPSUS$, which has claimed high-profile victims including NVIDIA, Samsung, Microsoft and Okta, are heavily focused on social engineering. Unlike most cyber extortion actors, both Scattered Spider and LAPSUS$ appear to be primarily located outside of Russia and other former Soviet states, with a reported presence in the UK, US and Brazil.

Both groups employ a variety of methods such as calling helpdesks pretending to be legitimate users, SMS phishing, SIM swapping and even bribing employees and contractors of victim companies. Both groups have extremely fast turnaround time from initial access to extortion.

Exploitation of vulnerabilities

Threat actors are increasingly seeking (and exploiting) vulnerabilities in the common digital platforms used by hundreds, if not thousands, of organisations. We have seen less and less lag time between a vulnerability being disclosed and attackers

exploiting it to target organisations across the globe at speed and scale. Where once security teams had perhaps days to patch known vulnerabilities, criminals and nation-states are now demonstrating the ability to actively exploit disclosed vulnerabilities within hours.

We have also seen some criminals invest considerable resources into zero-day development, something previously only done by nation-states. For example, in June, the Cl0p cyber extortion group claimed widespread exploitation of the MOVEit file transfer application as part of a global mass extortion campaign. This was the third mass exploitation of a file transfer application by Cl0p, and the second time in 2023 the group has been linked to zero-day exploit development. File transfer systems are particularly attractive to extortion criminals, since they’re gateways to data. It’s likely that Cl0p is developing more exploits for high value edge systems to facilitate future global data heists.

How are the criminals carrying out their attacks?

Increased evasion of detection tools

Post exploitation tools are now easily detected by host-based security software such as Anti-Virus (AV) and Endpoint Detection and Response (EDR). While we still see post exploitation tools, including malware-as-a-service and keyloggers, we have seen a decrease in Command and Control (C2) beaconing. Significantly, we have also observed an increased tendency to use built-in or already available and installed tools to reduce footprint and suspicion. This ‘living off the land’ technique is an example of how cyber extortion actors continue adapting to evade defences.

Better, more efficient tooling

We have observed a shift towards more efficient and feature-rich malware. For instance, the Lockbit 3.0 executable now features the use of a passcode for execution (designed to thwart reverse engineering), a group policy setting for easy lateral movement, and advanced anti-debugging features.[2]

Several ransomware groups, notably BlackCat, Hive and Zeon, have rewritten their tools in a relatively new programming language called Rust. Rust offers superior performance and provides excellent memory optimisation. This translates to quicker execution of malware, even on systems with low processor and memory resources. Rust-compiled ransomware is also a lot more complex to reverse engineer, making forensic analysis more difficult.

Hypervisor attacks

Hypervisors such as VMWare and HyperV that facilitate virtual machines are increasingly being targeted. Several ransomware groups now use capabilities to detonate ESXi (Linux) based ransomware executables directly on the hypervisor, encrypting entire virtual machine disks. This encryption is at the hypervisor layer; that is, attackers are encrypting raw disk sectors from disk images, rendering entire systems unbootable and unreadable, rather than encrypting only individual files.

What’s new in cyber crime extortion and “negotiation” tactics?

According to Chainalysis, the total value of global cyber extortion payments was at an all-time high in 2021 at US$939M and came down to about half that in 2022. But by mid-year 2023, the total payment amount was already at US$449M and may surpass the previous record. The dip in 2022 is likely related to the start of the Russia-Ukraine war and associated turbulence in the cyber extortion ecosystem.[3]

Over this period, CyberCX has observed a decrease in the number of organisations that pay. This coincides with a growing number of organisations assessing the payment of a ransom to be ineffective in minimising the harm of data theft extortion in particular rather than ransomware or double extortion). This trend is being offset by cyber extortion actors attempting to increase the scale and impact of their attacks.

Harm maximisation

Extortion criminals are adopting harm maximisation strategies to increase the pressure on victims to pay. These strategies affect all elements of the cyber extortion attack chain – from network discovery and staging data for exfiltration, to ransom negotiation.

We have observed threat actors:

- Spending longer in victim networks before data exfiltration to identify data that will cause the most harm if released.

- Filtering the most sensitive data and staggering its release to maximise media attention, as part of the ransom negotiation process.

- Publishing stolen data on the clear web (rather than only on the dark web) to increase the reach of stolen data, and associated damage, if victims don’t pay.

- Improving the public’s ability to search stolen datasets and to find individual records. For example, in June 2022 cyber extortion group ALPHV made it possible to directly search stolen data on both the clear and dark web, obviating the need to download entire datasets to examine them.

Misidentification of victims

We have observed an uptick in cyber crime groups misidentifying their victims. For example, threat actors have misidentified Australian victims on at least three occasions in the last six months. When victims are misidentified, stakeholders still expect transparent and timely updates, often before an investigation is finalised. Proving – and communicating about – a negative can be difficult. This highlights the need for organisations to ensure their playbooks for incident response, crisis communications and stakeholder management contemplate a scenario where a threat actor incorrectly claims – mistakenly or deliberately – to have hacked them.

Could you prove a negative? When a breach isn’t a breach

In mid-August 2023, the NoEscape cyber extortion group misidentified one of their victims as auDA, the .au domain administrator. An auDA investigation found no evidence of a breach or exposure of auDA-owned data. NoEscape had highly likely breached another entity and stolen data that merely referenced auDA. After auDA publicly disputed the claim, NoEscape reduced the negotiation timeframe from 8 to 3 days and released screenshots of alleged sample data, likely an attempt to still extort auDA, despite the misidentification.

Download the Best Practice Guide

Our Best Practice Guides offer clear, practical advice to improve organisations’ cyber security posture and resilience. We design these guides to be accessible for CEOs, boards, CISOs and professionals of all backgrounds.

Part 2:

Understanding and responding to an attack

How would an attack impact your organisation?

In CyberCX’s work with victim organisations, the most significant impacts from ransomware attacks are:

- Operational disruption, which can impact delivery of services to customers

- Lost revenue from missed business while operations were disrupted

- Loss of customers due to security or privacy concerns, exacerbating lost revenue

- Cost of response and remediation activities

- Cost of restoration from destructive attacks where data cannot be decrypted

- Reputational damage, including impacts on share value

- Costs incurred from failing to meet obligations to third parties, including penalties for contractual non-performance

- Personal impacts on staff, which are often overlooked, but very real

The impacts of responding to and recovering from a ransomware attack can be felt by an organisation for many months, long after the attack ceases. There are also other potential costs, including the risk of litigation by affected contractual partners and customers, which CyberCX assesses as likely to become more common.[4]

In the case of data theft extortion attacks, the most significant impacts include:

- Reputational damage and intellectual property loss if confidential data is exposed

- Loss of customers due to security or privacy concerns following notification of sensitive data being stolen

- Cost and possible operational disruption of response and remediation activities

- Impacts on individuals, including staff and customers, affected by any exposure of personal information.

Victims of data extortion may also be exposed to litigation risk and regulatory impacts, depending on the type of information that is exposed.

How long does a cyber extortion incident last?

The visible stages of an attack may not be evident for hours, weeks, or even months after an attacker gains initial access.

From the investigations performed by CyberCX, we see a wide range of timeframes between network penetration and obvious malicious activities, such as detonating ransomware. The variance depends upon a range of factors, including:

Expected return

The time taken to prepare an attack can be linked to profitability – that is, how much the criminals believe the ransom is worth. For a high-value target, criminals may spend a month inside the victim’s network to ensure their attack is successful. For smaller organisations, where access can be bought cheaply, attackers often operate more quickly, waiting only days, or sometimes ours, between initial compromise and obvious actions such as detonating ransomware.

Scope of access

Often we see a gap between initial access and later attack stages, which reflects the time it takes an initial attacker to escalate their initial access to a privileged level, or to sell or pass on their access methods to another criminal, who in turn leverages that access for subsequent attack stages.

Completing exfiltration of information

The length of this stage can depend on the complexity of the victim’s network and the steps needed for the attacker to avoid tripping security controls. In most cases, attackers only collect information which is readily available, such as documents in open file shares or emails and attachments in compromised mailboxes.

The attacker’s workflow

Sometimes attackers just get busy, or are distracted with other targets, especially in a large-scale campaign.

If an attack is caught early, there is still an opportunity to stop subsequent attack stages

CyberCX Intelligence aims to identify early signals that an organisation is a victim. Increasingly, we are working with customers to identify leaked credentials online, so that we can find them before a cyber extortion criminal does. In other cases, we are able to catch the attack after initial penetration, but before more damaging later stages. Stopping an attack in the early stages also increases the chance that the attacker does not pressure the victim organisation further, and simply moves on to another victim.

A cyber incident is like an iceberg – what you initially see is only a small part of an immense problem spreading throughout your organisation’s systems.

Attackers often compromise multiple systems, but not all these systems will show signs of compromise at the same time. This is why it’s important for the investigation to also cover systems which show no initial signs of compromise, including on-premise and cloud platforms.

For example, many organisations that have suffered a breach of their on-premise networks assume cloud platforms, such as Office365, have not been compromised because they are operating normally. However, attackers can often easily access Office365 mailboxes using stolen credentials to locate and steal confidential data that has been shared via email.

What are the stages of a cyber extortion attack?

The MITRE ATT&CK framework[4] provides a detailed understanding and reference for how cyber attacks are most often executed by attackers. Most attacks involve executing tasks within several stages. The below table focuses on stages most relevant to ransomware and data theft extortion attacks.

Stage |

Insights |

| Resource development

Including creation of ransomware program, data leak site and cryptocurrency accounts. |

Before an attacker can execute a ransomware or data theft extortion attack, they need to build or engage their network of affiliates and acquire some key elements to facilitate the attack, including:

This has resulted in the growth of ‘ransomware-as-a-service’ (RaaS), where attackers who develop these capabilities sell their use to other attackers. There are also ransomware developers who maintain bespoke ransomware for their own use or for their affiliates. |

| Initial access

Gaining initial access to the victim’s network. |

CyberCX has observed a growth in initial access brokers, criminals who specialise in gaining access to a network to share or on-sell that access to other groups for follow-on criminal activity.

The most common ways that we observe criminals gaining access are:

|

| Discovery

Gaining a detailed understanding of the victim’s network, to inform subsequent attack stages. |

The most common elements of the Discovery phase in ransomware and data theft extortion attacks include:

|

| Defensive evasion

Steps taken by attackers to avoid detection or delete evidence that could be used to reconstruct their actions. |

We now commonly find attackers employing defensive evasion techniques.

|

| Lateral movement

Accessing other computers and resources across the network. |

The extent of lateral movement is often driven by the need to either identify exposed data which can be encrypted or to steal confidential information for use in extortion. In most attacks, is the attacker achieves their objectives in this stage through a combination of network enumeration and the use of stolen credentials. During an investigation, it is vital to understand both:

|

| Collection

Finding and extracting sensitive information which can be used for extortion. |

In a ransomware-only attack, the attacker may skip this step.

Common targets for data collection include:

Financial records are sometimes of particular interest, since knowing facts such as the organisation’s revenue can benefit the attacker if the incident proceeds to negotiating a payment, as CyberCX has observed in several cases. Attackers commonly pilfer this information from target locations which are easy to access, the most common being:

CyberCX finds that attackers rarely target information through application platforms such as Customer Relationship Management (CRM) or document management systems, presumably because these require additional effort to access and navigate, and the effort to access these increases the risks of the attacker being detected. |

| Exfiltration

Extracting copies of sensitive and confidential data. |

We typically observe the attacker exfiltrating data to either their own systems (which may be a compromised system belonging to an unknowing third party) or a public file sharing platform.The volume of exfiltration will depend on several factors, including the time taken by the attacker to review and select material before exfiltration, the speed of their connection to the victim network and the time they are willing to let the transfer continue, while risking detection and possible disruption of subsequent attack stages. |

| Impact

Detonation of ransomware inside the victim’s network. |

The more data that ransomware can encrypt, the more effective the attack. More determined attackers will remain inside networks while they map out network structures and calculate the most destructive approach, although they need to balance this with the risk of being caught before completing all stages of their attack.

As mentioned above, attackers may also attempt to locate and delete or encrypt backups, rendering these ineffective as a means of restoration. |

The following stages are not included in the MITRE ATT&CK framework but are common in ransomware and data theft extortion cases.

Stage |

Insights |

| Engagement The attacker applies pressure to coerce the victim into paying their demands. |

Cyber criminals employ different strategies for advising victim organisations when an attack has occurred. Some will publicly disclose the breach and then invite the victim to negotiate, while others will engage the victim privately, providing them with the opportunity to resolve the incident without widespread public knowledge.

Some cyber criminals use additional techniques to contact victims or to apply further pressure, such as:

|

| Conclusion Incident response concludes. |

If a victim organisation decides to pay their attacker, they will usually be required to do so in cryptocurrency. This process can prove logistically difficult and, testament to the growing size of the cyber extortion economy, several legitimate third-party organisations now provide services to facilitate such payments. |

Resolution is not the end of the incident

It is important to remember that while response activities surrounding an incident may conclude, the victim organisation should not simply revert to ‘business as usual’. Post-incident activities often include:

- Detailed analysis of stolen data and reporting to required individuals and entities

- Dealing with ongoing legal matters, which may continue months or even years after the incident

- Recovering the organisation’s brand, reputation and lost business

- Remediating security vulnerabilities which contributed to the incident

- Conducting a post-incident review to identify areas where response was effective, and where improvements should be made

- Implementing security improvements to further lift the organisation’s security posture

- Actively monitoring for, and responding to, any future suspicious activities, especially similar to those identified through the investigation.

How different cyber extortion attack types impact organisations

In the last version of this Best Practice Guide, we compared the differences between ransomware and data theft extortion. In this updated version, we also assess the differences between these attack types and a third-party data breach. Increasingly, these attack types are interlinked – a data theft extortion for one party might be perceived as a third-party data breach by its stakeholders.

Third-party breaches can also result in an attacker ‘swimming upstream’ into your organisation’s systems and directly targeting your organisation with ransomware or data theft extortion.

Attack characteristics |

Ransomware |

Data theft extortion |

Third-party data breach |

| Involves compromise of the victim organisation’s computer systems. | Yes | Yes | No |

| Ransomware is ‘detonated’ inside a compromised network. | In most cases, this involves an attacker compromising systems, however it can also result from a data spill. | The attack happened outside of the organisation’s network, typically in a business partner. | |

| Causes disruption to computer systems and impacts business operations. | Yes | Maybe | Unlikely |

| The specific intent of ransomware is to disrupt the operation of systems. | Data can be stolen without disrupting the victim’s systems, however some disruption may still result from the attacker’s other actions, or from remediation activities. | However disruption is often caused by the time it takes to respond, understand the causes and impacts of the breach, and deal with enquiries from media, regulators and other stakeholders (including fourth-party victims). |

Incident response |

Ransomware |

Data theft extortion |

Third-party data breach |

| Can be responded to without widespread knowledge that the breach occurred. | Probably not | Maybe | Maybe |

| Encryption of systems will likely be visible to employees and will probably become publicly known. | Depends on whether the attacker chooses to post stolen data online before or during negotiations. | Third-party data breaches are often notified privately, however they can also become public when an entity is listed on the dark web or otherwise ends up in the media. | |

| Can be overcome by rebuilding damaged systems or restoring from backups. | Yes | No | No |

| However, this process can be lengthy and difficult. | Once data has been stolen, no remediation or restoration of the victim’s systems will bring it back, nor prevent its possible disclosure. | The damage is done outside of a network you control. | |

| Damage can be mitigated by paying the attacker | Probably | Maybe | Maybe |

| In our experience, cyber criminals often do provide working decryption processes – if they don’t, that damages their business model. However, there is no guarantee this will occur in every situation. | While attackers may provide assurances of data destruction, and some have strong records of doing so, they cannot provide absolute certainty. | However, unlike in a traditional data theft extortion case, you may not be able to directly engage nor negotiate with the attacker. | |

| Paying the attacker provides a guarantee that no further harm will arise. | No | No | No |

| When dealing with criminals, this cannot be guaranteed. | When dealing with criminals, this cannot be guaranteed. | When dealing with criminals, this cannot be guaranteed. |

Costs and impact |

Ransomware |

Data theft extortion |

Third-party data breach |

| May require costly and time-consuming rebuilding of damaged systems and networks. | Yes | Maybe | Unlikely |

| This process can be lengthy and difficult, depending on the complexity of systems and the integrity and completeness of backups. | While whole systems often don’t require rebuilding or restoration, security remediation is still required, and may be extensive. | You are probably outside of the technical blast radius. But there can be recovery activities (depending on the nature of the integration or what was breached). | |

| Requires security remediation to fix security weaknesses that contributed to the breach. | Yes | Yes | Unlikely |

| Remediation should be based on a thorough investigation to identify the full scope of the attack. | Remediation should be based on a thorough investigation to identify the full scope of the attack. | Remediation is mostly policy based – such as supplier security assessments and review of proactive notification clauses. But there may also need to be a review of data integration and security settings. |

Download the Best Practice Guide

Our Best Practice Guides offer clear, practical advice to improve organisations’ cyber security posture and resilience. We design these guides to be accessible for CEOs, boards, CISOs and professionals of all backgrounds.

Part 3:

Seven priority security controls

The risk of ransomware and other forms of cyber extortion cannot be entirely eliminated – but the risk can be mitigated. Organisations should review their security capabilities to ensure they are addressing the following seven priority areas.

Cyber security is a dynamic space. As the tools and tactics of cyber criminals evolve, the priority controls we recommend will evolve too. These controls are based on CyberCX’s real-world operational experience and are designed to be:

Practical

We understand that security controls are generally neither easy nor cheap, but we believe these baseline standards are accessible to all organisations.

Effective

These controls target the tradecraft we see cyber criminals repeatedly and successfully using to target organisations today.

Priority 1

Plan ahead to recover from a disruptive attack

Ensure the business can keep running.

Business continuity planning

Any organisation without a well-documented business continuity plan will have no choice but to improvise when a cyber security incident occurs.

The concept of Business Continuity Planning (BCP) has existed in the IT industry for decades, but has tended to focus on addressing system faults rather than a sentient attacker who will actively work against remediation efforts. In the current threat landscape, where cyber criminals are aggressively looking to damage systems and disrupt business operations, a holistic approach to BCP has never been more important.

Organisations should:

- Identify systems and data sources that are required to maintain critical business operations.

- Develop plans so that business operations can continue if these systems become unavailable due to a destructive attack.

- Develop plans for how to restore critical systems and data sources, including in what order of priority (it may help to think about both business needs and system dependence).

- Maintain multiple backups of each system in multiple locations, including at least one offline.

- Regularly test backups and continuity plans to ensure they would be effective if needed (considering both functionality and timeliness) and update as required.

- Ensure backups are protected from unauthorised destruction, including verifying backups before they are moved to offline storage.

Assessing ‘dwell time’ when restoring systems

A key consideration when restoring systems from attack is the attacker’s ‘dwell time’ inside the network; that is, the period between initial compromise and subsequent attack phases. If an attacker deploys malware or other mechanisms which provide backdoor access to a network, these may remain in place for days or weeks before subsequent attack phases. If a system is backed-up during this period, the backup may itself contain the same active backdoor. This can be addressed by:

- Conducting a thorough investigation to uncover the full scope of the attack

- Checking systems restored from recent backups, before putting those systems back into production.

Incident response planning

Don’t wait for a major incident to start developing your cyber incident response plan.

Organisations which invest some time and effort into preparing for a major incident manage real-life incidents better, with more successful outcomes. Having a predefined and approved incident response plan can minimise confusion and discoordination, especially in the critical early stages of a response. An effective incident response plan should identify:

- The participants and key stakeholders involved in an incident. A RACI model, categorising stakeholders as Responsible, Accountable, Consulted or Informed, can be helpful.

- The overall methodology that will be applied for responding.

- The high-level work streams that may be required

As any organisation that experiences a cyber incident knows, it’s not just “an IT problem”.

The most important element when establishing a cyber incident response plan is effective coordination and collaboration. A cyber incident can quickly escalate to become a major issue involving stakeholders across the organisation, up to senior management and board level.

Stakeholder management and communications plans

An organisation that can minimise the impact of a cyber security incident on its stakeholders can significantly minimise the impact on itself. In our experience, the most successful approach is to plan to provide timely and accurate updates on the progress of the investigation and restoration activities to all relevant stakeholders.

An effective stakeholder management and communications plan should:

- Identify all key stakeholders

- Determine for each stakeholder:

- expected role, responsibilities and/or actions

- what reporting is mandatory or otherwise necessary

- the appropriate contact person, and

- the cadence and method of communication

- Develop baseline communication statements based on investigation and restoration activities, then tailor communications for each stakeholder.

Technical incident playbooks

To complement the incident response plan, technical incident playbooks can be helpful for providing technical staff with guidelines on how to respond to specific incident scenarios. These playbooks should at least describe the actions required for initial identification, containment and triage investigation.

Conduct attack simulation exercises

An effective attack simulation exercise provides all the learning experience of a real-life incident but without the destruction. And it’s cheaper than paying a ransom. Attack simulations can take several forms, such as:

- Workshops for boards and senior executives, focussing on raising awareness of what would occur during a major incident, and working through key decisions that may need to be made, such as whether to engage with an attacker or make a ransom payment.

- Detailed technical ‘table-top’ exercises, which involve exploring a scenario of how a major incident could unfold on the network. Each step of the attack chain would then be assessed to determine what capabilities exist to prevent, detect and respond. This valuable exercise provides deep insight into the preparedness of the organisation and a clear roadmap for making improvements.

- Actual attack simulations executed on the network, such as ‘red team’ exercises which employ advanced attack techniques and ‘purple team’ exercises which include both attackers and defenders engaged in a ‘cat-and-mouse’ exercise to test both defence and response capabilities.

- These exercises should be developed and executed with the assistance of experts who can draw upon real-life experience and cyber threat intelligence, and be tailored to the unique technologies, confidential data, and business processes of your organisation.

Priority 2

Identify & protect your Crown Jewels

Understand your key systems and defend them appropriately.

All organisations should clearly understand what their most critical systems are, and organise their cyber defences accordingly.

1. Assess what systems are most critical for business operations

These may include applications specific to the business of the organisation or industry, and more common support systems such as email, file shares, and even basic internet access. It’s important to consider all critical systems in this assessment, as they may reside on-premise or in cloud platforms, and could be owned and operated by the organisation or by a third party. Part of this assessment should also involve considering how the business could continue operating if these systems were unavailable due to a cyber attack.

2. Determine how to defend them

Minimum security controls for protecting critical systems usually focus on ensuring that security configurations have been hardened, privileged access is tightly controlled and monitored, and technical vulnerabilities are quickly remediated.

3. Understand the dependencies

Understanding how systems are inter-dependent is essential to developing a realistic and achievable recovery strategy. Below are some common challenges we regularly see in real cyber attacks:

- CyberCX is increasingly responding to incidents against virtualised systems, where virtual machines are encrypted or hypervisors are directly attacked. In several cases, attackers are creating virtual machines on the organisation’s own virtualisation platform, which they use to carry out their attacks. Therefore it’s critical that virtualised environments and hypervisors are well secured.

- Authentication systems, in particular Microsoft Active Directory (AD) and increasingly cloud based Identity Providers (IDPs) are common targets for ransomware actors. Almost all enterprise-wide cyber attacks involve compromising and subverting AD to give the attackers privileges over the entire Windows Domain.Recovering or rebuilding AD is not a trivial exercise, often requiring full password resets and causing unexpected flow-on technical issues.

- Attacks which damage foundational network services such as DHCP (dynamic host connection protocol) and DNS (domain name service) can stop entire networks from operating. Organisations must ensure the configurations of these services are properly documented, backed up, and able to be restored quickly if needed.

- For organisations that rely on operational technology (OT), degrading adjacent or downstream IT infrastructure such as above can also force a loss of plant, machinery or other disruptions to operations.

Priority 3

Identify and address software vulnerabilities

Especially at the network perimeter.

The attacker should not be the first person to find your vulnerabilities.

New vulnerabilities are often identified in a wide range of common technology platforms such as remote access gateways, email platforms, firewalls, content management systems, file sharing platforms, online management portals and many more. The risk posed by these vulnerabilities quickly escalates when researchers or threat actors develop and publish exploits online.

Organisations should:

- Regularly scan their network perimeters for systems with known vulnerabilities Quickly remediate any vulnerabilities which are identified

- Ensure they receive all vendor security advisories for products they use

- Install vendor security patches in a timely manner

- Implement mitigating controls where patches cannot be applied

- Monitor systems for suspicious activities

- Ideally, for vulnerabilities on external- facing systems, organisations should patch (or mitigate) within 24 hours of any ‘proof of concept’ exploit being released online.

We get it: patching can result in operational downtime. But this must be weighed up against the operational downtime and significant other costs of a successful attack.

Too often, CyberCX responds to incidents after organisations delayed patching or scheduled a patch too late. Our advice is to adopt a risk-based, intelligence-led approach to patching. Organisations should prioritise patching vulnerabilities:

- Known to be under active exploitation or scanning by threat actors

- In outdated versions of software that no longer receive regular maintenance.

Priority 4

Fortify access points

Especially email and remote access.

A significant number of incidents CyberCX investigators respond to occur because organisations have not properly secured access points into their systems. This includes both on-premises networks and cloud-based application platforms. Organisations should:

- Identify all known access points, including those used by staff, contractors, customers and any third parties.

- Also identify system-based access points, such as endpoints used by application programming interfaces (APIs) which attackers could use to access systems and data.

- Scan the network perimeter regularly to identify any other unknown access points which emerge over time.

- Implement IP address filtering where possible. This should include blocking incoming connections from geographic regions that should not be connecting.[5]

- For systems requiring even greater security, controls such as specific source IP locking or client certificates can be useful.

- Employ effective multi-factor authentication (MFA) on all access points, and train users to recognise and report unsolicited MFA notifications.

Any remote access connection without MFA is a breach waiting to happen.

Monitor all access activity and investigate suspicious events. Any connection attempts that fail due to security controls such as geolocation filtering or MFA should be reviewed and investigated, with further blocking steps taken as necessary.

Priority 5

Prevent malware from executing inside your network

Use reputable EDR software and actively monitor your endpoint.

The best way to prevent ransomware is to shut down intrusions as early as possible.

It’s best practice to use an Endpoint Monitoring and Response (EDR) system. Compared with traditional anti-virus software, EDR systems include more advanced capabilities, such as collecting detailed endpoint telemetry, and allow for varying degrees of investigation and response to malicious activities.

However, just like any security capability, these systems are not ‘set-and-forget’ tools. They should be deployed as widely as possible, especially on all sensitive servers and user computers. They must also be properly configured and should be monitored closely to maintain high visibility of both normal and unusual endpoint activities, and all suspicious events should be investigated in a timely manner.

Priority 6

Clean up your organisation’s data

Don’t make it easy for attackers to steal your data. Audit what you’ve got, before it comes back to bite you.

CyberCX all too often sees data breaches made unnecessarily worse when too much data is available to the attacker.

Sensitive data builds up over time in computer networks: HR records, finance, payroll, customer data, and other sensitive information gets stored in repositories where it can easily be accessed

and exfiltrated for data theft extortion.

These can quickly make cyber breaches – and notifiable data breaches – larger and more painful than they need to be.

When it comes to your organisation’s data hygiene and governance, it’s important to remember: you don’t have to protect information that you don’t hold onto.

Organisations should:

- Identify the most sensitive data the organisation holds

- Locate all copies of sensitive data, not just those in obvious locations

- Restrict access to sensitive data on a ‘least needs’ basis, only giving access to those who absolutely need it

- Monitor access to the most sensitive data, and investigate suspicious access

- Wherever possible, archive or delete old copies of sensitive data from the network, so they are not readily available for opportunistic attackers to steal.

Organisations should pay particular attention to personal information they hold and use.

Beyond technical controls, this might also require organisations to carefully review what information they collect in the first place.

Organisations should:

- Understand what personal information is, and identify where it is stored, both inside their networks and in any third-party environments they use, such as online software platforms

- Only collect personal information needed to carry out their business

- Ensure personal information is only used in ways for which they have a legal basis (for example, with consent)

- Permanently destroy or de-identify personal information when the legal basis for holding it has expired.

Priority 7

Manage privileged access and closely monitor its use.

Don’t make it easy for attackers to steal your data. Audit what you’ve got, before it comes back to bite you.

A key objective for most attackers is to obtain access to privileged accounts to effectively carry out their attacks.

Most activities across a network occur within the context of an “account”. This is why they are such a valuable targets for attackers.

Organisations can counter this by both closely managing access to privileged accounts and monitoring their use. Attacks against privileged accounts are synonymous with attacks against authentication systems, the most notable for ransomware being Active Directory (AD), the security heart of a Microsoft Windows network

Specifically, organisations should:

- Allocate separate privileged accounts to users and not allow them to be shared

- Provision privileged accounts with the minimum level of permissions required

- Ensure that privileged accounts are not used for everyday activities, such as web surfing or viewing emails, and are only used strictly when required

- Prohibit privileged accounts from directly accessing the network remotely

- Ensure that all privileged accounts require strong authentication and MFA to access

- Closely monitor the use of privileged accounts and identify suspicious usage, such as from unusual external sources, at odd times of day, or with unusual frequency

- Also closely monitor changes to privileged accounts, such as their creation or reconfiguration

- Alert and investigate suspicious use of privileged accounts

- Harden systems which provide authentication and account security, especially Active Directory

- Review access controls on a regular basis and remove unnecessary privileges

This same rigour should be applied to any third-party IT providers used by an organisation. Such providers are often given privileged account level access to an organisation’s systems to perform their duties. This could prove to be a significant risk factor if the third-party provider follows poor protocols such as sharing administrator passwords among different team members.

Download the Best Practice Guide

Our Best Practice Guides offer clear, practical advice to improve organisations’ cyber security posture and resilience. We design these guides to be accessible for CEOs, boards, CISOs and professionals of all backgrounds.

Part 4:

Engaging with your attacker

When and why should organisations engage with their attacker?

There are reasons for engaging with an attacker other than to negotiate a payment

There are reasons for engaging with an attacker other than to negotiate a payment. Depending on what an organisation aims to achieve, engagement can be established at various stages of an attack. It can provide some degree of control over the situation, while the organisation determines the best course of action. It can also be used to obtain information that complements evidence recovered by forensic investigators which can help defenders respond to the attack or protect themselves in the future.

Key objectives of attacker engagement include:

- To stop the attacker conducting further malicious activities

Many attackers will attempt to gain the victim’s attention soon after executing the final, obvious stage of an attack, such as deploying ransomware. They may send emails to senior executives or large groups of users, directly contact the organisation through public phone numbers or launch denial-of-service attacks against the organisation’s website. Some attackers will post samples of stolen data on their data leak sites. Once an attacker has been engaged, they will often pause these activities while engaging with the victim organisation.

- To confirm what information was stolen from the network

There are two key ways to confirm what information was stolen from a network and both may need to be performed in cases where this has potentially occurred:- Locating evidence through a forensic investigation

- Obtaining proof directly from the attacker

In a forensic investigation, this can be one of the more difficult elements of an attack to reconstruct, since it relies on evidence of exfiltration still existing and being complete.

- To know when the attacker will publish stolen data online

Engaging with an attacker provides a degree of insight into their next steps and timeline. While engaging in a genuine dialogue, there is less chance that stolen data will be published online.

- To learn about the attack (or not)

Although a forensic investigation can reconstruct most steps in an attack, its completeness is based upon the availability and completeness of evidence. If any investigative questions remain unanswered, these could be solicited from the attacker.Many attackers will provide details of the attack after receiving payment. Some will even offer security remediation advice to prevent future similar attacks. However, in CyberCX’s experience, attackers are often inaccurate or incomplete with the information they provide. This may happen for various reasons, including attackers wanting to protect their methods, or because the criminals conducting the engagement don’t actually know how the breach first occurred.Importantly, the advice of a criminal should not be used as the sole basis of formal investigation reporting nor future security remediation.To confirm the ability to decrypt data.

- Most attackers will offer to decrypt sample files as proof that it can be done. Care should be taken when supplying sample files, to ensure that viable ‘proof-of-life’ is obtained. Samples files should:

- Be chosen by the victim organisation, not the attacker

- Contain no personal or confidential data

- Be specific to the victim organisation

- Have contents which can be reasonably identified when decrypted.

CyberCX has seen cases where attackers have used complex encryption processes which cannot be undone across every file, even using the attacker’s own decryption programs. In these cases, the attacker can usually prove decryption of small data files, but their decryption fails on large data such as databases, backups and virtual machines.

- To get decryption keys or prevent publication of stolen data

The final reasons for engaging with attackers are the most obvious:- To negotiate the purchase of a program that can be used to decrypt files and recover systems.

- To obtain agreement that the attacker will destroy stolen data and not post it online.

Principles for success

- “It’s not personal, it’s just business”

Cyber criminals generally want one thing – to monetise their attacks with minimal effort and conflict. Cyber criminals often apply the “it’s just business” approach to their communication and negotiation. We find that adopting a similar approach helps organisations achieve the best outcome, whether they choose to pay attackers or not.

- Cyber criminals are just that – criminals

While cyber criminals may provide assurances, and even have strong reputations for keeping their word, they cannot provide absolute certainty regarding their actions. It’s important to remember that you’re dealing with criminals, therefore there are no guarantees.

- Treat your communications as if they could be made public

Cyber criminals will seek to exploit any angle or opportunity to gain leverage over a victim organisation, including potentially leaking part or all of their communications with you, especially if they are not paid. Bear this in mind to ensure everything you communicate is defensible and would not cause embarrassment or harm if made public.

- Attackers read the news too

Some attackers will keep a close eye on communications from a victim organisation, especially in cases where the incident attracts significant media attention. Victim organisations need to be mindful of any major disconnection between what they say to the attacker and what they say publicly.

- Obtain professional help

Victim organisations will be best supported by a professional services firm with operational experience both assisting victims and engaging with cyber criminals, and with access to high-quality threat intelligence. In non-cyber ransom or extortion cases, law enforcement and professional agencies provide advice, engage and communicate with the offenders, and complete any resolution. Cyber versions of these crimes should be treated the same.

- Don’t rush

Organisations are often more inclined to pay ransoms in the early stages of an incident when the perceived impact is most dire. Attackers often employ tactics to create pressure on the victim organisation to pay at an early stage because they know that the more time that passes, the higher the chance that the victim organisation chooses alternate paths to resolution, which do not involve paying the criminals. Ultimately, organisations should conduct negotiations on their own terms and on their own timeframe – having a clear incident response playbook ahead of time (per Part 3) and using the decision aids set out in Part 5 can help victim organisations keep the initiative.

- Make intelligence-informed decisions

While every attack is different, cyber intelligence can inform decision-makers about:- Who the cyber criminals are

- How they are known to operate

- How best to approach engagement and (if needed) negotiation

- What to expect in response to the victim organisation’s actions

- What to expect if they are, or are not, paid.

- Every attack is different and every attacker will behave differently

Many of the major cyber crime groups are composed of affiliate members, so even subsequent engagements with the same group can play out in different ways. Threat intelligence about a cyber crime group is valuable and should be factored into decision-making, but it does not provide absolute certainty about what will happen next.

Principles for Staying safe

Establish private communications

Most attackers will provide an initial channel to engage them in further communications. This will often be a link to their dark web site, but some groups operate email addresses through platforms that provide high levels of security and anonymity.

Organisations should consider the privacy of any communications. In many cases, if an attacker provides a link to an online chat function on their dark web site, anyone with that link (for example, a user who found a ransom note on the network) can often see the transcript of the discussion. It is therefore worthwhile asking attackers to move communications to other channels.

Maintain personal security

Cyber criminals will not identify themselves – neither should you.

Another important strategy when dealing with cyber criminals is to remain anonymous. They only need to know they’re dealing with someone who is authorised by the victim organisation to deal with them. Personal safety is important; they should not know the identity of the person they’re dealing with.

Download the Best Practice Guide

Our Best Practice Guides offer clear, practical advice to improve organisations’ cyber security posture and resilience. We design these guides to be accessible for CEOs, boards, CISOs and professionals of all backgrounds.

Part 5:

Should you pay a ransom or extortion demand?

Why are we having this conversation?

CyberCX does not condone or encourage paying cyber criminals. But we recognise that, in some situations, organisations feel compelled to consider paying a ransom. We also know that there is limited (if any) information available to assist organisations in making this difficult assessment.

As we discussed in Part 1, the frequency and impact of cyber extortion is rising. At CyberCX, we want to see organisations able to defend against and respond effectively to these crimes.

We also support a major step-up in law enforcement action against cyber criminals, including to disrupt their operations. If we all do our jobs well, many of the difficult considerations set out in this section may cease to be relevant. However, this section of the Best Practice Guide reflects the reality of today’s threat landscape and the difficult choices victim organisations are facing every day.

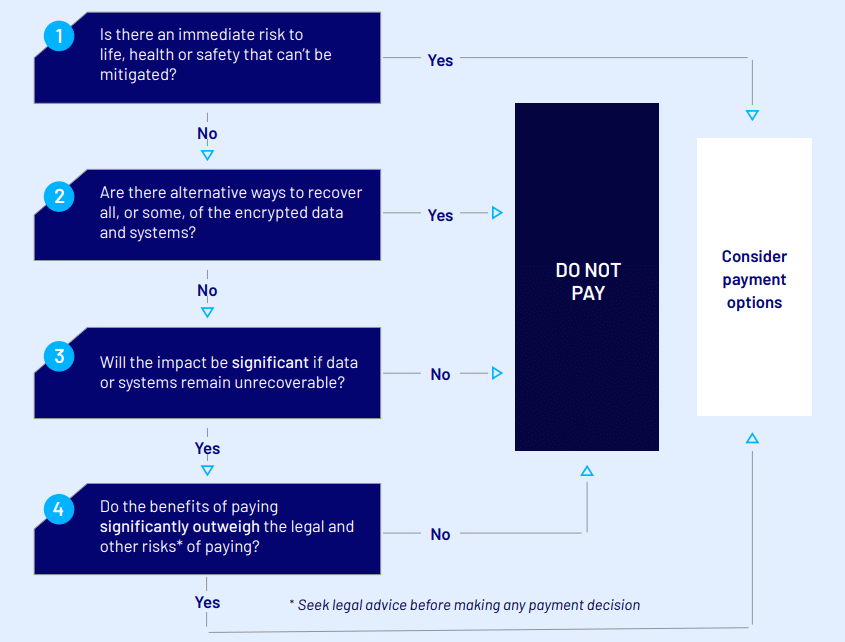

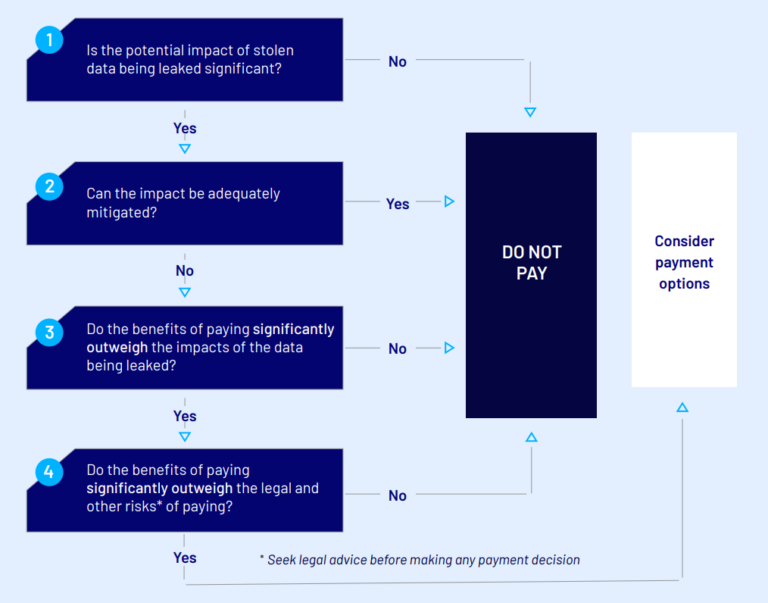

The following decision framework relates to situations where systems and data have been encrypted or made inaccessible by ransomware. Further below, we present a similar framework for situations where sensitive data has been stolen.

Quick guide: In the event of a ransomware attack

Should you pay a ransom?

If faced with a ransom demand, victim organisations should consider the following.

Are there alternative ways to recover all, or some, of the encrypted data and systems?

- Can you restore from backups?

Backups may still be compromised, since attackers may have been present inside the network when backups were taken, but before data was encrypted. Therefore, backups need to be checked and possibly cleaned after restoration. This may be possible, especially in situations where the attack was not executed cleanly, and data was not properly encrypted. In several cases, CyberCX investigators have used forensic techniques to recover damaged data without needing to engage the attackers.

- Can you recover encrypted files through forensic methods?

This may be possible, especially in situations where the attack was not executed cleanly, and data was not properly encrypted. In several cases, CyberCX investigators have used forensic techniques to recover damaged data without needing to engage the attackers.

- Can you rebuild systems from base installs?

This could include a hybrid approach where operating systems and applications are built from scratch, then production data is imported from backups.

- Can you collect data from other sources?

Common sources include out-of-schedule backups, users or developers who may have stored local copies, or business partners who may have their own copies.

Exploring options for recovering your data or systems can take days or weeks. This phase does not need to be completed before engaging with the attacker.

Do the benefits of paying significantly outweigh the impacts of not recovering any residual encrypted data or systems?

- What are the possible benefits of paying the attacker for decryption?

Assess the benefits of a possible restoration of remaining encrypted data

- What are the residual operational impacts of data that cannot be recovered?

Major impacts may include:

- Risks to personal health and safety caused by system disruption

- Lost revenue while operations are disrupted

- Contractual penalties for impacted delivery of products or services

- Upstream or downstream costs of interrupted operation

- What’s your legal and regulatory risk?

Possible legal risks arising from a ransomware attack include:- Risk of contractual claims or litigation resulting from operational interruption and breaches of contractual obligations

- Litigation by customers, shareholders and affected parties

- Regulatory action and fines due to a breach of a regulatory or licensing obligation

- Do the benefits of paying significantly outweigh the risks of paying?

Victim organisations should assess:- Moral and ethical considerations, including that payment will almost certainly fund future criminal activity

- The Australian, New Zealand, UK and US government cyber security agencies all advise against paying a ransom. [6] The New Zealand Government has formally mandated a policy that government agencies do not pay ransoms [7]

Do the benefits of paying significantly outweigh the risks of paying?

- Risk that the decryption method may not work on all data or systems. This risk can be partially mitigated by:

- Intelligence about the attacker ideally tailored to your specific national, sectoral and organisational context

- Having the attacker prove the decryption method

- Risk that the attacker will not provide a decryption method. This risk can be partially mitigated by:

- Having the attacker prove the decryption method

- Intelligence on the history of successful recovery after paying the attacker

- Reputational harm or brand damage. This risk can be partially mitigated by effective crisis communications and stakeholder management.

- Legal risks, such as:

- Ransom payments may be illegal and attract civil and criminal liability under local and international laws. This can include laws prohibiting making any form of financial payment to individuals or organisations that are subject to sanctions.

- Any organisation that is considering making a ransom payment should seek legal advice before making any decisions, as a payment may not be legally defensible depending on the circumstances.

What’s the risk of the attacker returning if I do pay the ransom?

Evidence on this question is varied. In CyberCX’s experience, we have found that cyber crime groups rarely return for repeated attacks against the same victim organisations, whether they pay or not.

In our experience, if the victim organisation properly responds to the incident and remediates the security vulnerabilities that contributed to the breach, the chance of an attacker returning is significantly reduced.

CyberCX has not seen strong evidence that paying a ransom makes an organisation more of a target for future attacks. We have observed cases where organisations in Australia and New Zealand were attacked by different cyber crime groups in reasonably short succession. In some cases this occurred despite the victims strongly refusing to pay the attackers. We have also observed repeated attacks due to initial access brokers providing the same compromised network access to multiple parties.

Quick guide: In the event of a data theft extortion attack

Should you pay a data theft extortion demand?

Unlike ransomware, where paying a ransom could yield a decryption key, paying a ransom in data theft extortion cases can never be a complete reduction of risk. Once the data genie is out of the bottle, it’s impossible to return. Nonetheless, some organisations might consider paying to limit the likelihood and places their data is exposed, especially if their data is extremely sensitive. If faced with a data theft extortion attack, victim organisations should consider the following.

Is the potential impact of stolen data being leaked significant?

Determine what data was or may have been accessed or stolen Review and categorise the accessed or stolen data to determine how to respond

Note that it can take days or weeks to investigate whether and what data was accessed or stolen. This investigation phase does not need to be completed before engagement with the attacker. In fact, engaging with the attacker may inform this process, for example by obtaining proof of the information they claim to have stolen, although attackers should never be trusted as the sole source of evidence.

Review and categorise the accessed or stolen data to determine how to respond

Any data which has been accessed or stolen should be collected, catalogued, and prepared for searching and review by the investigation team. The data should be divided into the following four categories:

- Personal Information (PI)

Personal information is any information about an identified or identifiable individual. It can include data about a person which on the surface does not identify an individual, but which can reasonably be used to identify who it relates to through data matching, or through existing or attainable knowledge of a potential recipient. Determining ‘what is personal information’ requires assessing the sensitivity of the information and understanding the corresponding privacy risk. This often requires advice from a privacy expert. Many organisations have contracts in place which require notification of data breaches that may affect information related to third parties. In some cases, these requirements may allow third parties to access investigation records or even conduct their own independent review of the incident.

- Third-party confidential information

Many organisations have contracts in place which require notification of data breaches that may affect information related to third parties. In some cases, these requirements may allow third parties to access investigation records or even conduct their own independent review of the incident.

- Organisational confidential information

This includes information such as research and development, trade secrets or confidential financial data. It may also include confidential internal communications, meeting minutes, and other material that, while not being reportable to any third party, may create significant risk if exposed.

- Security-related information

This includes any information that could be used to further compromise the organisation’s environment, such as technical details of computer systems and networks, system documentation, source code (which can provide a wealth of sensitive technical information), passwords and secret keys, operational technologies, physical premises and assets, and even the security of people.

Do the benefits of paying significantly outweigh the potential impacts of the stolen data being leaked?

- What are the possible impacts of stolen data being published online?

For each of the categories of information above, assess the impacts of it being made public, and potential subsequent misuse, accounting for any actions taken to reduce these impacts.

- What are the possible benefits of paying the attackers to not leak the data?

This assessment should be informed by threat intelligence on the attacker’s history of publishing or not publishing data following to payment.

Most attackers will not publish stolen data online after being paid, which some organisations feel is sufficient to justify payment. However, there are no guarantees that the attacker will also destroy the data or not allow it to be reused for further harm.

Do the benefits of paying significantly outweigh the risks of paying?

Victim organisations should assess:

- Moral and ethical considerations, including that payment will almost certainly fund future criminal activity.

- The Australian, New Zealand, UK and US government cyber security agencies all advise against paying a ransom.[8] The New Zealand Government has formally mandated a policy that government agencies do not pay ransoms.[9]

- Risk that the attacker will still leak data. This risk can be partially mitigated by leveraging intelligence on whether the attacker has a history of not publishing after payment.

- Risk that the attacker will still monetise or otherwise use the data, for example by selling it to other cyber criminals such as initial access brokers or to a foreign government. This risk is difficult to mitigate.

- Reputational harm or brand damage. This risk can be partially mitigated by effective crisis communications and stakeholder management.

- Legal risks, such as:

Ransom payments may be illegal and attract civil and criminal liability under local and international laws. This can include laws prohibiting making any form of financial payment to individuals or organisations subject to sanctions. - Any organisation that is considering making a ransom payment should seek legal advice before making any decisions, as a payment may not be legally defensible depending on the circumstances.

- It is important to note that even if an attacker does not publish stolen data, and claims to have deleted it, victim organisations may still have obligations to report the data theft to regulators, affected individuals and other stakeholders.

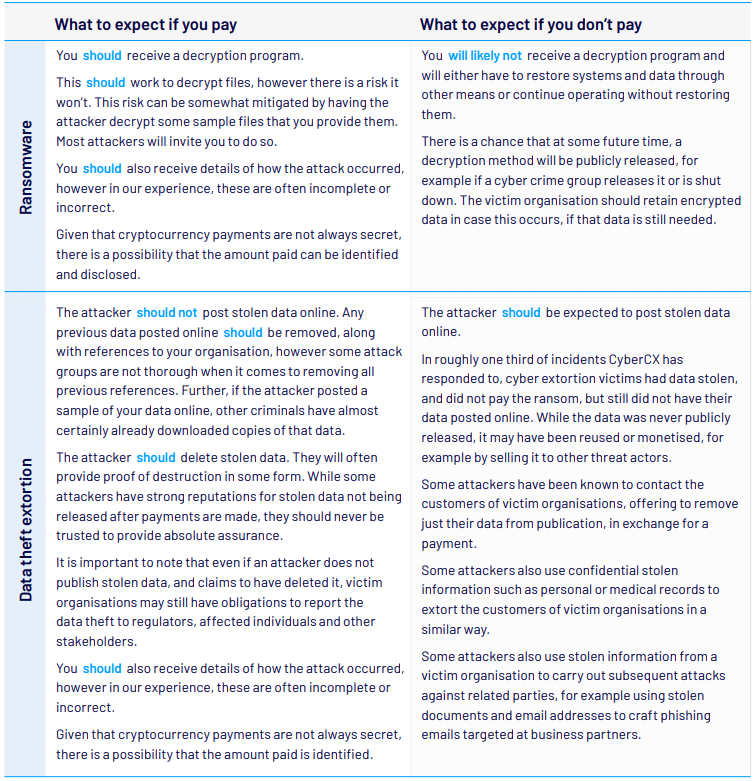

What should organisations expect if they do or don’t pay?

Download the Best Practice Guide

Our Best Practice Guides offer clear, practical advice to improve organisations’ cyber security posture and resilience. We design these guides to be accessible for CEOs, boards, CISOs and professionals of all backgrounds.

“ We believe all organisations should have access to strategies and tools to uplift their cyber security and improve resilience.”

Alastair MacGibbon, Chief Strategy Officer, CyberCX

Our Best Practice Guides leverage CyberCX’s significant operational and advisory experience, including:

- Experience from incidents responded to by our Digital Forensics & Incident Response (DFIR) practice across the Indo-Pacific and globally.

- CyberCX Intelligence, a unique Indo-Pacific intelligence capability which leverages global open and closed sources, creates unique first-party regional intelligence, and actively monitors dark web and criminal marketplace forums.

- Insights from our Cyber Strategic Communications team, which advises senior leaders in many of our region’s most high-profile incidents.

- Insights from CyberCX’s Security Testing & Assurance (STA) practice, the largest security testing capability in the region.

- Telemetry collected by our Managed Security Services (MSS) teams monitoring client networks across Australia, New Zealand and globally.

- Insights from our Strategy & Consulting (S&C) and Governance, Risk & Compliance (GRC) practices on cyber security strategies, investments and risk management, and how leading organisations protect their most critical assets.

References

[1] In December 2020, Cl0p exploited vulnerabilities in the Accellion File Transfer Appliance, compromising an estimated 50 organisations worldwide. In January 2023, the group exploited a vulnerability in the GoAnywhere Managed File Transfer (MFT), compromising approximately 130 organisations. In June 2023, they commenced their campaign exploiting a zero-day vulnerability in the MOVEit MFT, compromising over 500 organisations.

[2] https://securityaffairs.com/149941/hacking/lockbit-3-leaked-code-usage.html

[3] https://www.chainalysis.com/blog/crypto-ransomware-revenue-down-as-victims-refuse-to-pay/

[4] https://attack.mitre.org

[5] This control alone can be bypassed by a capable attacker but is still worthwhile and often easy to implement on remote access platforms. If a small group of staff travel and need access from remote locations, these should be configured as exceptions and ideally allowed only when needed.

[6] https://www.cyber.gov.au/threats/types-threats/ransomware

[7] https://www.dpmc.govt.nz/our-programmes/national-security/cyber-security-strategy/cyber-ransom-advice

[8] https://www.cyber.gov.au/threats/types-threats/ransomware

[9] https://www.dpmc.govt.nz/our-programmes/national-security/cyber-security-strategy/cyber-ransom-advice

Key terms

Cyber security is a fast-moving industry and sometimes terminology changes quickly too. In this Best Practice Guide, we use some key terms as outlined below.

A type of malicious software designed to “scramble” information, making data or systems unusable unless the victim makes a payment.

The individuals and groups involved in committing different elements of these crimes, including those who develop malicious software, gain unauthorised access to victim networks, deploy ransomware, steal information and engage in extortion. Attackers are also referred to as Threat Actors.

An overarching term for any crime where the confidentiality, integrity or availability of a victim’s computer systems or data are damaged or threatened unless the victim makes a payment

A type of cyber extortion involving theft of sensitive information and threats to expose it unless the victim makes a payment.

A type of cyber criminal who specialises in gaining access to victim networks to share or on-sell that access to others for follow-on criminal activity

Download the Best Practice Guide